Review: Deep Web Tries to Unravel the Mystery of Silk Road

Still from Deep Web

The title of actor and director Alex Winter’s engrossing new documentary, Deep Web, contains multitudes. It primarily refers to a place, that obscure no-man’s-land on the Internet that goes unseen by the majority of users. It also alludes to another, more literary meaning. In traditional true crime reportage, if you pull the thread, the truth will unravel. Not so in this tale, though. When you pull the thread you just find more thread; a deep web that goes on forever.

The film, which I saw at this year’s SXSW, follows the story of Silk Road, a notorious underground marketplace for drugs and illicit goods that was shut down in 2013 after raids by multiple federal agencies. The site existed in the “dark net,” part of the “deep web” that goes unseen by the vast majority of connected users. Think of the Internet as an iceberg. Part of it sits just above water, visible to all. This is where we shop and download music, chat with friends, and read blogs. Below the surface, though, is an expanse exponentially greater in size and almost unfathomably, well, deep. It’s a place where everything from Oxycodon to rocket launchers can be purchased anonymously. When you connect to the dark net, there is nothing that ties you to an IP address; you have no identity, no nation. It is in this notorious pocket of the unseen Internet that the film takes place.

The Silk Road was something of an online Souk, a cacophonous nook of the world where nothing was above haggling, and where almost every drug imaginable could be purchased as easily as ordering paper towels off Amazon. Marijuana, cocaine, heroine; all could be ordered anonymously from the comforts of home, with a package arriving inconspicuously a few days later. The site relied on Bitcoin, the popular cryptocurrency that allows for anonymized transactions (if you’re careful). Since Bitcoin, like Silk Road, is nationless, it acts like an invisible dollar, keeping every aspect of the sales on the site undetected.

According to the Silk Road sellers interviewed anonymously for Deep Web, the site was also a community built around libertarian ideals. The idea was to make the sale and purchase of illicit items so dead simple, there would be no need for turf wars. Some on the site believed they could end the drug war by taking violence out of the equation completely. Perhaps the most illuminating point on the topic, featured in the film, comes from a 2012 episode of the Julian Assange Show, a roundtable discussion web series on RT that ran throughout that year. The episode featured noted “cypherpunks,” or cryptographic activists, including Tor developer Jacob Appelbaum, who says this:

Force of authority is derived from violence. One must acknowledge with cryptography, no amount of violence will ever solve a math problem.

In other words, since you can’t break down the door of an algorithm, violence is suddenly removed from the equation. The users of Silk Road were looking to do an end run around the drug war. In hindsight they proved unable to avoid that “force of authority” Appelbaum refers to. The government caught up with them.

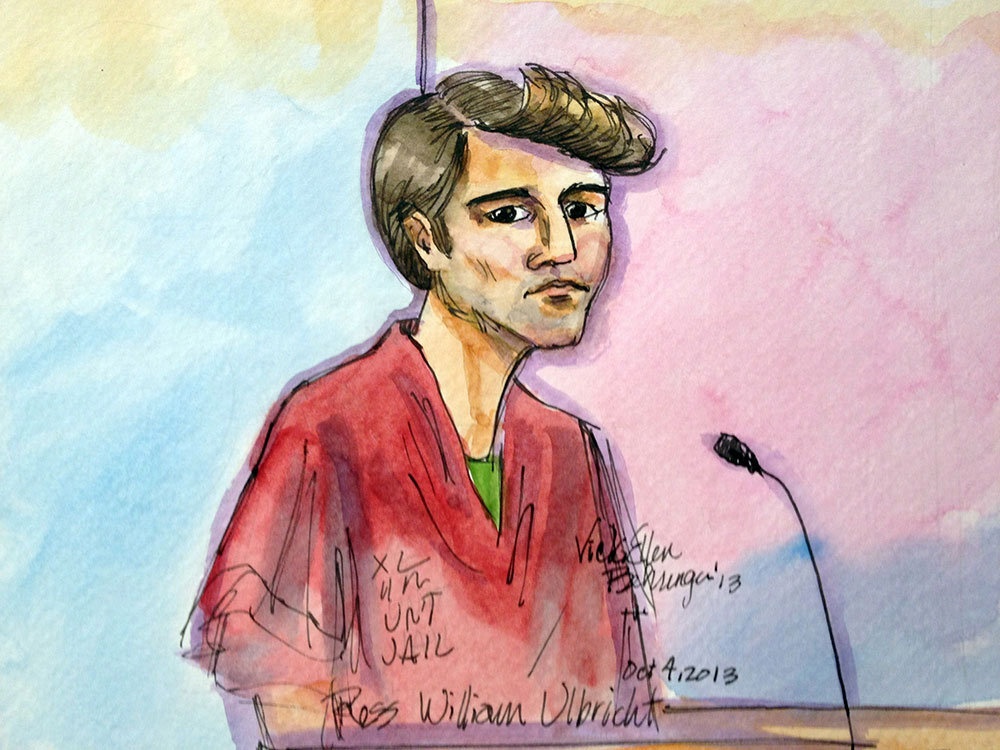

Which brings us to Ross Ulbricht, the 30 year old whose current legal predicament lies at the heart of Deep Web. Earlier this year, Ulbricht was convicted of being a “digital kingpin” for running Silk Road under the pseudonym Dread Pirate Roberts, or “DPR,” the protagonist from William Goldman’s The Princess Bride. Just as in the book and popular film, “Dread Pirate Roberts,” is a title, not a name, belonging to whoever holds the position at present. Even though Ulbricht has been convicted, questions still loom over his exact role in Silk Road, and whether or not he was, in fact, the DPR. According to one Silk Road seller interviewed in the film, the DPR account, like the literary anti-hero, did not represent a single person. It was passed down from user to user, and was maintained by multiple people as well. So was Ulbricht the kingpin, or merely the fall guy?

The film offers no real answers because there are still so many murky details about Silk Road. To cite just one glaring example, there’s the issue of a federal agent who infiltrated the site using the name “nob.” Nob not only communicated with whoever was running the DPR account, he was supposedly contracted by DPR to commit murder for hire. Whenever DPR asked an enemy to be rubbed out, the federal agent would send photos of a staged murder. Ulbricht was pilloried in the press when his arrest was made public for this. Not only was he accused of being the head of a massive, international drug enterprise, but he was supposedly behind brutal, mob-like murders, even though the murders never actually occurred. In fact, when federal prosecutors brought their case against Ulbricht, no murder-for-hire charges were brought against him. Ulbricht’s defenders believe this was a calculated ploy to allow him to be found guilty in the eyes of the public before bringing charges against him.

In late March, an even stranger twist in the tale of Silk Road was revealed. Nob, the federal agent who staged the murders, was actually a DEA agent named Carl Mark Force IV. Force, who, along with Secret Service agent Shaun W. Bridges, deposited bitcoins extracted from Silk Road in the course of the investigation into his own personal account. The agents used the anonymized nature of their investigation to their advantage, keeping encrypted conversations and transactions from their superiors.

The version of Deep Web that EPIX will air this weekend will have an end title briefly explaining the stunning turn of events regarding Force and the federal corruption that came to light only after Ulbricht’s convition. The card will likely change further as Ulbricht recieved his sentence today: life in prison.

Deep Web raises more questions than answers, not just about Silk Road and Ulbricht, but about what is fast becoming one of the defining struggles of our times. Are we prepared for the crypto-revolution? When everything is encrypted and anonymous, what rule of law is there? As more and more of our lives become digital, what scrutiny, government or otherwise, are we opening ourselves up to?

The technology that allowed Silk Road to operate so successfully also enabled corrupt government agents to extort money for personal gain. In our digital future, who are the good guys? Winter’s film exposes us to the idea that it’s getting increasingly hard to tell.

Deep Web premieres on EPIX this Sunday, May 31st, at 8:00pm EDT.