No Grand Gestures

There’s plenty to talk about in yesterday’s earnings letter from Netflix (embedded below). The big number is 810,000, the amount of subscribers the company lost last quarter. The shareholders’ letter is grim, repeatedly referring to the recent customer exits as a “wave”. The language sounds as though the company is bloodied and limping towards a revival. The starkest line, in my view, is this:

In the U.S., we’ll build back our brand the same way we built it in the first place: no grand gestures, just amazing service day‐after‐day, for an incredibly low price.

Build back? This is not the language of, as is the company’s stated aspiration, the “best streaming video subscription service on the planet.” Their stock is plummeting, customers are exiting en masse and new competitors are cropping up. Is this the end of Netflix? Not exactly.

There is a silver lining for the company. Domesitc revenues were up year-over- year, as were their profit margins compared to the last quarter. The reason? Less DVD shipments and, of course, the increased price of DVD-only plans. In other words, their goal of being the best streaming service is meetable; DVD and Blu-Ray seekers are marginal. If physical discs are your preferred method of watching films, Netflix doesn’t care about you anymore.

I know this specifically because of this “no grand gestures” line. I have said before CEO Reed Hastings should have dealt with this issue more like Steve Jobs dealt with the iPhone 4 “antenna-gate”; with a sweeping good-will deed (free bumpers!) that made customers content enough to stick around. Though Netflix’s letter has a plain-spokenness to it, there are also bits that sound delusional. The above “incredibly low price” is a start, but elsewhere they complain of being perceived as “greedy” in light of the price increase. The problem, Hastings asserts, is that they did a poor job of explaining the pricing changes.

The letter is also dubious about the threat of competition:

Our $7.99 pricing is a full 20% lower than our nearest unlimited DVD‐by‐mail competitor, and our service is better because we have more distribution centers and, as such, faster delivery.

They are right about the leg-up on delivery speed, but the pricing comparison with (I assume) Blockbuster is misleading. Yes, Blockbuster’s cheapest plan is $9.99 a month, but it includes Blu-ray discs and videogames. The monthly price for a single unlimited Blu-ray plan from Netflix? $9.99.

As a Netflix customer I have this much to say to Reed and CFO David Wells: you are wrong. The time for chest-thumping bravado is over. We have had nothing but excuses since you announced the price increase this summer. People aren’t leaving because of a botched e-mail, it’s because you have proven that there is a wide swath of customers you have no regard for. We are waiting for you to make a move that says you are not abandoning lovers of physical discs, which is to say lovers of library completeness and audiovisual quality. We are all waiting for that grand gesture. Until we can’t wait anymore.

[Netflix Investor Letter Q3 2011](http://www.scribd.com/doc/70219146/Netflix- Investor-Letter-Q3-2011)

Are Americans Ready for The Infidel Sitcom?

Josef Adalian reports for New York Magazine’s [Vulture](http://nymag.com/daily /entertainment/2011/10/nbc_will_try_to_bridge_the_dif.html):

Are American TV viewers ready to flock to a network sitcom that explores questions of faith and ethnic identity, not to mention the often tense relationship between Muslims and Jews? …Vulture hears the Peacock is working with Avalon Television to develop a small-screen adaptation of last year’s British comedy film The Infidel, which had its U.S. debut at Tribeca and then played here largely via cable video on demand platforms.

I got to see the comedy when it came to New York for the Tribeca Film Festival. Here’s what I had to [say at Heeb](http://heebmagazine.com/chosen- film-the-infidel/5496):

Comedy should be confrontational, and The Infidel crosses the line more than a few times. Still, the light style somehow keeps even touchy political and religious conflicts breezy. Like Bend it Like Beckham, the moral is “Be yourself, hey, but blend just a tad.” That wrap-up might be a little too simple for some, but without it the film would devolve into the same old arguments that both peoples have been warring over for millennia.

The question as to whether or not American audiences are ready for a comedy about religious strife on television is a valid one. After all, The Infidel played in New York on the eve of the furor that was the Park51/Cordoba House project in lower Manhattan, one of the most volatile issues during the summer of 2010. During the festival, I had sit-down interviews with director Josh Appignanesi, writer David Baddiel and stars Omid Djalili and Richard Schiff.1 You can [listen to the full interview](http://www.candlerblog.com/2010/04/29/candlercast-16-a -conversation-with-the-infidel-team/), but I think some of the excerpts below shed some light on their approach to perceived controversy.

I suggested to both Appignanesi and Baddiel that the film goes too far in terms of controversial imagery, specifically one scene in which Djalili appears in a concentration camp uniform. They had this to say:

David Baddiel: If you actually deconstruct that particular gag, it’s not a guy who just appears in a concentration camp outfit and the audience laughs because he’s in a concentration camp outfit. It’s a Muslim who’s having a nightmare about the idea that he is Jewish. His subconscious, comically, is projecting himself as various Jewish monstrosities. To me, the one you’re going to end on there is that one.

Josh Appignanesi: What’s particularly funny about that is that the monstrous things that you might imagine Jews to be involve them being the worst victims of the twentieth century. There’s kind of quite an inverted joke if you look at it closely and it’s quite a subversive joke.

DB: It’s also about an anxiety. When he goes to the computer and puts the word Jew [in a search engine] and gets a lod of hate back at him, that is real. Google had to change it because there was so much anti-semitism that came off the web. The point is with Mahmud it’s something that hasn’t really occurred to him. First he finds out that he’s Jewish and that’s a problem for his identity, then he has to deal with the fact that, if you’re Jewish, you will have anti-semitism to deal with.

JA: And you’ll have the Holocaust as part of your history.

DB: For me, with any joke, it’s not just like “Okay, you can’t make jokes about that thing.” I never think that. What I think is that you have to look at the individual joke and the context of that individual joke and say, “Okay; or not.” There’s still going to be people that think it’s not okay because they think some subjects are untouchable. All subjects are touchable within contextual grounds.

I asked whether or not it had met much resistance in the UK.

JA: People keep saying, “It’s controversial,” but then, actually, it’s not really clear where the controversy is. They sort of think it will be somewhere else but not for them. They might feel, “A bit edgy. That was maybe a bit close to the bone, but I don’t find it really problematic. I liked it.” Then who do they think will find it problematic? It usually ends up [they think] Muslims will find it problematic because they might kill you, because of Salman Rushdie, because of whatever. Because of South Park now2, because there are reactive parts of 1.1 billion people. There are a lot of Muslims out there, some of them are bound to be nutters.

In the UK we had some worries because [neither myself nor David] are Muslim. We had some Muslim people helping out on the film…producers, consultants for the script and stuff, but we didn’t know for sure and we were a little worried. They’ve embraced it more than anyone. That’s our big immigrant population is essentially Muslim or if not Muslim then “brown” people who get stopped at airports because of what’s been happening in the world and so identify with this character.

What became clear instantly is how seriously the creative team took this material. The reason the film feels “breezy” is because they didn’t just run with the same joke for the film’s duration. The idea of a Muslim man waking up to find he is a Jew could easily be both offensive and funny, but they didn’t create the film to push people’s buttons.

But will it play on American television, especially after the film hardly played in the US? I think it can work, and Baddiel’s involvement in the project is certainly reassuring. However, it’s tough to forget how divided we are in this country on issues of religion. The Park51 incidents of 2010 and this year’s [Koran burning](http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/02/world/asia/02afg hanistan.html?pagewanted=all) by Florida pastor Terry Jones don’t bode well for an American public primed to comically approach its differences.

I’ll bet that Jews and Muslims would be the least offended by the actual material if they saw it. More likely, as Appignanesi mentioned, it will be condemned on the grounds that the Muslims will blow us up for it. Thankfully, these guys realize that a powder-keg that big must be confronted. Why not in sitcom form?

-

Right now, it appears [Baddiel and Djalili are involved](http://www.deadline.com/2011/10/nbc-developing-comedy-series- version-of-british-film-the-infidel-starring-omid-djalili/) in the development of the NBC project. ↩︎

-

Shortly before the film played in New York the [creators of South Park had received a death threat](http://www.guardian.co.uk/tv-and- radio/2010/apr/22/south-park-censored-fatwa-muhammad) from an extremist Muslim Web site based out of New York. ↩︎

Lytro Camera Could Change the Purpose of Focus, But Why?

Last week we saw the introduction of the first commercially available light field camera, the Lytro. But what’s a light field? From the company’s site:

The light field is a core concept in imaging science….It is the amount of light traveling in every direction through every point in space….

Recording light fields requires an innovative, entirely new kind of sensor called a light field sensor. The light field sensor captures the color, intensity and vector direction of the rays of light.

Because the Lytro camera can record all of the available light in a scene, it can capture all possible focal points. When you use it to take a picture, you just click and you’re done. Worry about focusing the photo later.

Here’s a sample. Click around the frame to refocus the image:

{::nomarkdown}

The technology here is pretty incredible, but it’s based on the premise that taking the time to focus a photo while shooting is time wasted. The light field camera takes the concept of point and shoot to its most literal level. Changing the focus after the shot has been taken isn’t just a tool to correct poorly focused shots. One major feature of the Lytro is that you can share your photos with an embedded viewer like the one above, allowing anyone to change the focus of the photograph. Manipulating the focal point then becomes part of the experience of viewing the photo; the viewer can become the photographer.

Focus is a funny thing. It wasn’t so long ago that photographers were unsure whether or not they could trust the autofocus engines in their cameras. Some even wrote it off as a fad. Autofocusing lenses are bigger, louder and heavier than their manual counterparts and they suck up more battery life to boot. The trick of the technology, the real magic of it, is that it can figure out what you want to focus on. Every time the shutter button is half-depressed, the camera processes thousands of conceivable photographic setups, matching those against the color and contrast of the light coming through the lens and using that information to figure out where the likely focal point is. Then it whips the lens’s elements into the correct position for a sharp focus. All of this happens in an instant. The faster the better.

The trouble with auto-focus is that it doesn’t always know the look you’re going for. It gets uncannily close most of the time for most types of photos, but what about more stylized scenes, when an unnatural focus is part of the photo’s allure? What about when focus is used by the photographer to obscure or frame the photo’s subject?

Every image is a narrative, its many parts selected, for better or worse, by the person behind the camera. Framing, focus, exposure and a host of other factors lead to a finished image. Depending on how dense your image is, there can be a bevy of focal points from which to choose from. The photographer’s decision to choose what is in focus and what isn’t is all part of the creative process. The question will now become, if focus doesn’t matter in the moment, what do you take a picture of?

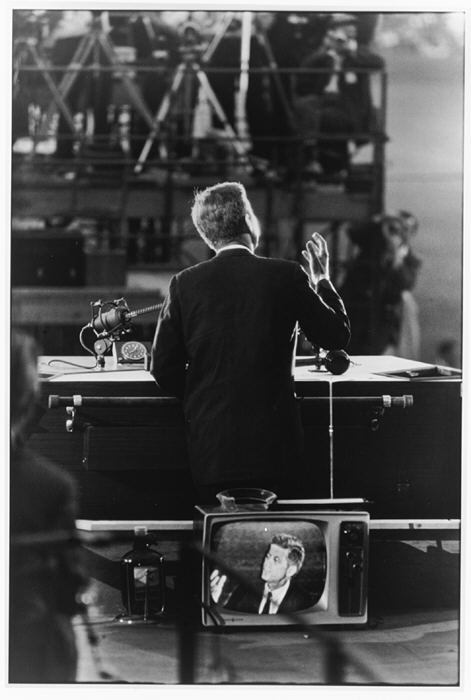

Here’s an example of a photo whose narrative could be completely altered by the use of a light field camera:

John F. Kennedy, Democratic National Convention, 1960. Garry Winogrand

Here we have three or four relative focal lengths. Each one tells a different story. There is the rail-work in the foreground, which helps set the stage but is mostly set-dressing. Then we have the television set with John F. Kennedy’s face, followed immediately by the candidate’s backside. Then we have the abyss, the crowd and the television cameras and the (other) photographers. Would we have anything to gain by being able to post-process this photo and move the focal point? The narrative would definitely change if Kennedy were obscured and the crowd in focus, but to what end?

“Boy With the Bottles” Rue Mouffetard, Paris, 1954. Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Take this Henri Cartier-Bresson photo of a boy carrying wine bottles. Imagine changing the focus to the girl in the background. It would change the photo’s story, but would it be a better one? Would having the ability to see both focal points enhance the photo? I’m not sure, but it’s worth considering.

I imagine that photographers will quickly realize that the best light field photos are ones that have multiple narratives depending on where the viewer chooses to set the focal point. The above embedded image is a great example of this style, showing off how a photo’s layers can change how you feel about the image. Otherwise, why should anyone take the time to refocus the picture themselves?

Allowing those who view your work refocus the image makes them part of the photographic process. Does this then mean that artists will be able to be less deliberate since the audience can correct for their mistakes in the image? Has focus just been a nuisance, a means to an end, all these years? Or must photographers now be more deliberate in order to make the photos worth tinkering with?

I can’t help but wonder what the implications of the Lytro are for cinema. If this technology were able to be applied to the moving image, perhaps one day audiences will be able to change the focus of a scene while viewing a film. Each viewer would have an active, unique experience while watching the film. Again, to what end? Imagine being able to change the focus in the tent scene in David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. Below are stills from a single shot in the seminal sequence.

Lawrence of Arabia Animated Tent Sequence

The examples I’ve used here are from a bygone era, long before light field sensors would make it possible to shoot without focusing. Perhaps finite focus isn’t a problem that needs correcting. Or maybe we’re moving into a completely new era in photography. Either way, I can’t wait to see what creative photos people come up with once the Lytros start shipping.

Israel's Oscar Choice

I had the pleasure this past week of seeing two great new Israeli films, Nadav Lapid’s Policeman and Joseph Cedar’s Footnote. The latter is Israel’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar this year and it also ran away with almost all of the 2011 Ophir Awards (the Israeli Oscar analogue). I’m not sure if Policeman ever came close to getting the nod for Oscar, but it was nominated for top honors alongside Footnote so I can’t imagine it wasn’t considered.

The task of selecting a film to represent a national cinema at the Oscars is a daunting one. On the one hand, you want to select a film that represents your country and the state of its film community. It is a statement, on some level, of national representation and values. On the other hand, you want to submit something that has a chance of getting nominated. Even if a film doesn’t win, the nomination helps promote a country’s movie business. So the question may as well be asked: between Policeman and Footnote, which is a better snapshot of Israel and its film community today?1

Policeman is a slow, haunting story that depicts the separate travails of both an anti-terrorism police officer and a small band of Israeli extremists. Through acts of violence, the one swears to protect what Israel stands for while the other vows to change it by any means necessary. The terrorists are outraged by the economic disparity in Israel, a point that should stick in any viewer’s gut when they look at the massive protests that took place in Israel this past summer and those that are ongoing on Wall Street today. It wouldn’t be such a stretch to say that Lapid’s film moved hordes of Israelis into the streets to speak out against policy they can longer abide by.

Cedar’s Footnote is a high-brow Talmudic comedy of errors, a smart take on Judeo-intellectualism and the state of modern discourse. It is a also a sweet, at times too sweet, story of a father and son. It tells the tale of two Professor Shkolniks, Eliezer and his son Uriel. Both are Talmud scholars at Hebrew University, but the son’s achievements outshine those of the father. Though its moving parts are of particular interest to a Jewish audience (there’s a nice flourish about the death of Judaism by way of Zionist machismo), its core is wholly universal. Moreover, Footnote doesn’t go near the ongoing military and political struggles of Israel. The only thing keeping this story in the holy land is its relationship to the Talmud. Of the two films, it’s certainly the more accessible one.

I think both are excellent films. In the end I have to wonder which film I would rather represent me, not as a Jew or on behalf of Israel, but which speaks to me and which I would like to share with others. And this is the predicament. On a technical level, I find Policeman the more interesting film for its deliberateness and its tackling of seemingly untouchable material. However, I wonder if I’m getting caught up in the zeitgeist of the Occupy Wall Street movement and economic unrest across the globe. In 20 years, which film will still be available and worth watching? I don’t know.

In the end, it is Footnote that the powers that be have chosen as a national champion. It’s a worthy competitor and it may well nab the Oscar spot. Make no mistake, though, Policeman is also a great representative of what is churning in the Israeli psyche. If you have to choose between the two films here is my advice: don’t. See both.

-

I should mention that I don’t know the inner workings of the selection of an Israeli film for the Oscars. The producers of Policeman may well have abstained. ↩︎

NYFF '11 Review: The Artist

Michel Hazanavicius is a master of the homage. By that I mean he is an incredibly well-versed movie nerd, approaching cinema history as gospel; the movie house his cathedral. His latest film, The Artist, is a love letter to Classical Hollywood Cinema, that bygone era since obliterated by the New Hollywood filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s. The film follows the travails of a silent film actor during the rise of sound in the early 1930s and is itself a silent film, in black and white, in the legacy 1.37:1 aspect ratio.

It seems there is a question as to whether or not audiences will actually go and watch a silent film, but I think it’s a foolish thing to wonder about it. There was a golden age of silent cinema for a reason. We have outgrown that form but we’re not immune to enjoying it. If you can get a modern moviegoer to sit down and watch Battleship Potemkin or, better, The Last Laugh, I think that most people would actually have an enjoyable time. The form can be timeless, but Hazanavicius offers us something much more palpable than reminiscing over times gone by. He has given us a film that is eminently watchable, engaging for both the armchair historian and the blockbuster-goer alike.

In cinematic terms, modern conventions have allowed filmmakers and audiences to lull into laziness. Widescreen formats, color film and bloated soundtracks have allowed us all to neglect convention without much consequence. A terrible cut can be corrected (or bandaged) with the right sound effect; a vertical frame is more difficult to fill than a wide one; black and white art direction can be more nuanced than color.1 Where some may see nothing but challenges in silent filmmaking, Hazanavicius sees opportunities. Like a blind man who elevates his hearing, Hazanavicius’ other sensibilities congeal to become pitch perfect. The Artist is an exercise in montage, a wonderful use of imagery to tell a story that is exciting, new and repeatedly surprising.

I should mention the most exuberantly non-silent aspect of the film, the music of Ludovic Bource. Much in the way that Hazanavicius is a master of cinematic homage, Bource has composed an impeccable score that shines throughout the film. The music rises and dips and twirls with our main character. Just like the visuals, the music is both modern and derivative (sometimes explicitly). It’s absolutely charming and the film would be nothing without it.

The question remains: will anyone actually see The Artist. I most certainly hope so. At its core, it is a heartfelt film with all of the elements modern moviegoers enjoy at the movies: love, drama, laughs and a spunky Jack Russell Terrier who deserves an Oscar nod. If people aren’t lining up to see it, it will be a real shame.

-

There are some gross generalizations here, I realize. I’ve been trying to find a clip of François Truffaut speaking about widescreen formats and how it changes how he directs actors, but I’ll have to settle for this one in which he talks briefly about color versus black and white film. ↩︎

NYFF '11 Review: Corman's World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel

It’s a real shame when I tell people “I just saw a documentary about Roger Corman” and they ask “Who?” Who? Somehow Corman has been pushed to the wings of the story of American cinema. The much ballyhooed “New Hollywood” of the 1970s may never have come of age without him, yet his name has been all but rubbed out by the stars who would outshine him. Alex Stapleton’s excellent Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel aims to put the spotlight back on the man who changed the game for generations of filmmakers.

Roger Corman’s greatest talent has been making movies, and I mean that in the most literal sense. The number of films with his name attached is astounding, perhaps approaching one thousand by this point.1 Corman turned his operation into a well-oiled machine, one that could make films in less than a week. His goal was never to re-invent the wheel, the thing that holds up the Stanley Kubricks and the Paul Thomas Andersons of the world, but to be able to make as many movies that could find an audience as possible.

His stylings led him to be one of the most successful B-movie and exploitation producers of all time, but there is a lot more to him. As it turns out, he is rather offended by his reputation as a maker of trashy camp. As Stapleton’s film explores, his life’s work has been less about making “bad” movies and more about making films that tap into what audiences want. Yes, that has meant a lot of breasts and a lot of explosions, but also a lot of work that, even when it was forgettable, became the training ground for some of the world’s top talent. Jack Nicholson, Ron Howard, Jonathan Demme and Francis Ford Coppola are just a few of the names to have found their start under Corman’s tutelage.

But what of the documentary at hand? Stapleton has made a great biography of a man who history may soon forget. Even though his work is both prolific and extremely accessible today2 he is still somewhat unknown among younger generations of cinephiles. Stapleton’s film elegantly, and enjoyably, moves to correct that. It also tries to explain it. Just as it seems the book is closed on Corman, Stapleton introduces a new villain: Steven Spielberg. One of the film’s conceits, sparked by those close to Corman, is that Jaws and Star Wars represented a major shift in the way the studios went after younger audiences. These were basically Corman movies with massive budgets, and it all but put him out of business, or at least pushed him into obscurity.

It’s an interesting theory, but I’m not so sure I believe it. It’s often said that those blockbusters were the turning point, downward, for American cinema; they’re the reason why there are nothing but loud comic book movies in theaters today. The biggest hole in that theory is that if the studios found a way to attract audiences with Corman-esque films, couldn’t Corman simply step in and become more successful? If Stapleton trips here, it is only because she is too enthralled with her subject.

Nonetheless, Corman’s World is an excellent watch and a damn good time. The doc features excellent closing credits in the grindhouse vain and a number of artistic interstitials (enjoy the poster montage). Interviews with stars big and small, young and old make for a great Hollywood tell-all, but the best footage comes from a wonderfully unguarded interview with Jack Nicholson. If you love Corman, don’t miss this one; if you don’t know who he is, get your ass to a theater and learn something.

Corman’s World will be screening as part of the New York Film Festival on Sunday, October 16 and 1:30pm with a special screening of Corman’s 1962 The Intruder starring William Shatner. For more information check out the NYFF’s website.

Drive's Judaism

⇓ Updated October 20, 2011 in the comments. ⇓

This morning I posted a piece over at Heeb Magazine about Sarah Deming, a Michigan woman suing FilmDistrict, distributors of Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, over being misled into seeing a film.

That’s a great and ridiculous story to run with from the start, but there’s more. The Hollywood Reporter reports:

“Drive bore very little similarity to a chase, or race action film… having very little driving in the motion picture,” the suit continues. “Drive was a motion picture that substantially contained extreme gratuitous defamatory dehumanizing racism directed against members of the Jewish faith, and thereby promoted criminal violence against members of the Jewish faith.”

I kept things light and funny over at Heeb, but I have to be honest, this stuff really pisses me off. I’m offended as a film lover, as an American and as a Jew. Where to begin?

L et’s start with the whole misleading trailer business. This is what happens when we put all our faith in movie trailers and Rotten Tomato scores; this is what happens when our culture abandons hope that an act of cinema might occur when the lights go down. I’ve resisted doing trailer reviews for as long as I’ve been blogging because I know how and why they are made. Trailers are marketing tools that generally have nothing to do with the filmmaker or the final work.

While there is an art to cutting a trailer, it’s important to recognize that, usually, trailer editors are given a set amount of footage hand-picked by the marketing department. Sometimes they get explicit instructions how to cut the piece and often don’t get to see the whole film before they begin. That’s because trailers are a marketing tool designed to get butts in seats and that’s all. Is it misleading to put all of Drive’s action into the trailer? Not at all. You want more information before you go see it? Read a review.

As to the implication that Drive is anti-semitic, I’d counter Deming’s accusation with this argument: Refn’s film is perhaps one of the most positive Jewish films in 2011. There is a long history of victimization of Jews in cinema, so I’m impressed whenever I see a film that puts power in the hands of some Hebrews. The characters in question, Bernie (Albert Brooks) and Nino (Ron Perlman) are mobsters looking to make a dent in the business of their gentile counterparts.

Their religion, or rather their culture, is what redeems them, what makes them worthy adversaries to Ryan Gosling’s nameless Driver. Why is Nino such a son- of-a-bitch? Because he’s been trying to make it ahead in a world where he gets called “kike” and slapped around. That backstory is what makes him relatable, what makes him something more than a throw-away baddie.

If that’s not enough to bring you around to liking the film then that’s fine, but don’t come out swinging with misinformed accusations because you’re annoyed. There’s plenty to hate in Drive. Frankly I thought the film was more violent than I expected. I even agree that there wasn’t enough driving given the film’s title. But so what? If I can’t get my money back for The Scorpion King then, Sarah, you can’t have your money back for Drive. Get a clue or stop going to the movies.

NYFF '11 Review: My Week With Marilyn

Simon Curtis’s My Week With Marilyn is very much a Weinstein Company release. It is an impersonation romp more suited to the small screen than to the cinema. Replete with stunning performances, a corny soundtrack and uninspired technique, it is the stuff that the brothers Weinstein know how to spin into gold. And, much like The King’s Speech of last year, it will likely overcome its own mediocrity and dazzle awards voters all season long. It is the easiest answer to the Best Picture question.

Let’s start with the performances. Michelle Williams gets very close to brilliance portraying the incomparable Marilyn Monroe, a feat that shouldn’t (and won’t; see above) go uncommended. As complicated as Monroe was in her own time, her image has been Xeroxed, caricatured, overdone and parodied to death since her passing. It would be too easy for Williams to do Marilyn burlesque, a sort of recreation of the woman through her on-screen manifests. Thankfully, she becomes something more; a woman playing the part of the woman she wishes she could be.

The role, however, falls short of illuminating too much outside of what the dialogue spoon-feeds us. Throughout the lumbering screenplay we are told that Marilyn is a broken woman who uses up the people around her. We wait for her to pulverize our hero, the young Colin Clark played by Eddie Redmayne. Colin is the son of an aristocrat who wishes to run off and make movies, eventually landing a gig as the third assistant director on a new film by Sir Laurence Olivier starring Monroe. Olivier is played by Kenneth Branagh, a Briton who has earned a stature similar to the man he is portraying. Much like Williams, Brangh does his damnedest to sidestep farce and imbue his Olivier with only the slightest hint of homage, bringing out a spark of something more than the man we would see so many times on screen.

So, young Colin Clark finds himself amidst giants, with the greatest actor in the world teaming up alongside the hottest commodity in Hollywood. And he has seemingly unfettered access to both. Marilyn shows up late to set on a regular basis and is always accompanied by a cabal of handlers, the most vocal of whom is her acting coach, Paula Strasberg (Zoë Wanamaker). In a bit of backstage cleverness, this matchup of stars sets up a clash of acting styles. Monroe is fascinated by Colin who treats her as a woman instead of as a piece of meat. And so the two frolic for a fleeting period, at the expense of Colin’s untimely meet-cute with a wardrobe girl, Lucy (Emma Watson).

Since the Curtis is winkingly telling a tale of the filmmaking process (method acting’s rise, on-set union clashes, a new age of celebrity worship, etc.) perhaps it would have done him some good to revisit Syd Field or even Aristotle. The story is shoddy and the characters learn nothing. Worse, very little is at stake for our young hero who is forced to choose between beautiful and most beautiful. An aristocrat trying to make a name for himself can be a compelling story, but in this case Colin has so little to lose we have no reason to care. His love of Monroe never transcends schoolboy infatuation, yet we are expected to believe him when he asks the starlet to run away together. It’s going to take a lot more than charm and sweater-vests to bark up that tree.

With all this talk of story, I should perhaps be lambasting screenwriter Adrian Hodges, but I’m not so sure that’s where things first went wrong. There are a lot of elements of the story that could work and play instead as missed opportunities. The culture clash of actors abroad and the mental state of a young Monroe (before Some Like it Hot, before Kennedy) are brilliant fodder for a great story. All of the pieces are there on screen but they never cohere into something that goes beyond lecturing; they never form together to make cinema.

The fault then, I suspect, should lie with director Simon Curtis, but perhaps there is more at work here. I can’t get over how similar this film feels to The King’s Speech. Stylistically on almost every count, even down to those damned wide lenses, Marilyn mimics the prior film. Can it be, then, that the Weinsteins are to blame? Harvey has a long history of watering down films in order to land an Oscar, but I think that process has now flipped around, inviting filmmakers to keep their aspirations in check and take the easiest route possible. It’s a real shame, because there’s a great story trying to break through here, with a world-class cast dying to do good. Unfortunately, it never comes together into something more than “just okay.”

Qwikster Goeth, or What the Hell is Going on at Netflix?

Netflix is making it real hard for customers to keep cool and stay confident that they know what the hell they are doing. After botching a summer price hike, confusing customers and initiating an exodus of 1 million customers, CEO Reed Hastings came out and made a large-scale public apology last month while announcing a new DVD-only company called Qwikster, turning Netflix proper into a streaming only service. Today, Hastings is backtracking. In a blog post, he succinctly lets us know that Qwikster is canceled and that Netflix will remain unchanged.

It is clear that for many of our members two websites would make things more difficult, so we are going to keep Netflix as one place to go for streaming and DVDs.

This means no change: one website, one account, one password… in other words, no Qwikster.

I was uneasy about the price hike, and frustrated by the Qwikster announcement, but I understood it and gave Netflix the benefit of the doubt. Now, not so much. Now, I’m pissed.

Whenever I write about Reed Hastings, I tend to paint him in a visionary light, and it’s all well deserved. He upended an entire industry and built a company with incredible customer service. However, Reed has never been tested like he has this year. I think it’s now safe to say that he failed.

Customers wanted to be reassured that the company they love wasn’t going to screw them. That’s what Reed’s Qwikster announcement was all about. He said all the right things in a tone people can respect. He put his foot down and said the company is going to take a major chance. Netflix bet the farm on the future.

Less than a month later the entire plan is undone. What new information could there possibly be after a few weeks that Hastings and company couldn’t foresee when they set this up?

Let’s pretend that they are responding to the biggest customer complaint regarding managing two different queues and ratings/reviews accounts. That functionality was expressly explained by Hastings in his announcement. If they didn’t see it as a problem until after the Qwikster announcement, what else are they missing?

There is the unlikely possibility that all of this was actually a smart move. Perhaps (and that’s a big perhaps) Netflix was trying to wave a big stick in the face of the studios, to let them know that if they don’t get serious about making streaming pacts they are willing to break up the company at the studios’ expense. The metrics of this conspiracy theory don’t entirely add up, but that’s the only positive explanation I can think up for these erratic moves.

Reed, you fucked up in July. Then you fixed it in September. Now you fucked up again.

The only olive branch left to offer customers is a price cut or at least a rebate of some sort. Look at how Apple dealt with “antenna-gate”. They never admitted culpability, but they spent some money on free bumpers so that they could sell a ton more iPhones and restore confidence in the company.

I have little confidence that Netflix has a clear vision for the future anymore. I doubt I’m alone. It’s time to win back customers and quit shooting from the hip.

Wouldn't it be Called iPhone 6?

People keep saying that the iPhone 4S is an iterative bump while the next big iPhone redesign will be released in 2012 under the name iPhone 5. Wouldn’t it actually be an iPhone 6? Dig:

- 2007: iPhone

- 2008: iPhone 3G

- 2009: iPhone 3GS

- 2010: iPhone 4

- 2011: iPhone 4S

The next iPhone will in fact be the 6th iPhone model ever.

Apple didn’t do themselves any favors by naming their second phone “3G”. Almost every non-tech nerd I know doesn’t realize that there is a difference between the 3G and the 3GS and most call last year’s model the iPhone 4G. It’s the most confusing naming convention in Apple’s lineup.

I hope they move to a different convention before the next phone comes out. Perhaps make the flagship iPhone an iPhone Pro and flip the iPhone 4S to just plain iPhone and leave the iPhone 3GS as 3GS until it goes out of production.

I don’t know where they’ll take things next, but iPhone 5 is numerically inconsistent and iPhone 6 is just confusing. Gotta change the name eventually.