Intriguing Possibilities: Not-So Accidental Network

Why write about The Social Network now? When advances occur it usually takes time to appropriately access the real nature of any advancement, so of course it should take the appropriate amount of time necessary before this analysis and comprehension. After giving Fincher’s latest masterwork the amount of time given internet-advancement, that with which I conclude is an unexpected sympathy for Fincher’s sculpting of Zuckerberg, or I should say Fincher’s sculpting of Marylin Delpy’s sympathy of Zuckerberg. Wait, who is Marylin? This question is part of the point, in time…

?While most have focused on the Citizen Kane aspect of the pseudo-biographic nature of the narrative (and appropriately so, despite Fincher’s denial of such) and have often overlooked the title’s allusion and thematic extensions of opportunism and the communication-industry’s pessimism in Lumet’s Network, Fincher’s work has decisively specific additions that go beyond a contemporary portrait of the “time” and provide a caveat of the “time’s” problematic future.

?While Zuckerberg is viewed through the eyes of an accessor, that of his attorney associate Marylin Delpy, she immediately links together the historical and factual elements that support a simplistic biographic rendering. What is unique about Marylin’s conveyance of Zuckerberg is her specific goal: to conclude the manners in which Zuckerberg may be viewed as slightly autistic, an opportunistic asshole, or simply obsessively reaching towards vengeance. Marylin’s drive to match historical moments with these tendencies are what structure the scenes of the narrative’s past: Zuckerberg being impersonal when relating to dorm mates about girls, his dismissive attitude towards Eduardo almost every other scene, his condescending demeanor in the company of businessmen or authority figures. If each one of these scenes were to be entered into evidence, they would imply and support any of the previous personality traits theories. This uniquely places Marylin in the position of editor/director, in which she guides the audience through time/space, allowing us to view through her evidence-glasses to convey the worst-case depiction of character.

What this structuring implies is a need to define and explain situations/facts to complete Marylin’s argument that “Zuckerberg is a terrible person, and here’s why.” What this simplistic rendering does not allow is identification with Zuckerberg, since Marylin’s approach is driven to combat the opposing attorney’s case and a sympathetic drafting would not win the lawsuit. Without the recognition of Marylin’s point of view the audience is left with a despicable character study that would alone imply a wrong and limited depiction of a real person; Zuckerberg becomes just an unsympathetic protagonist, or as “symbolic” for the limits of the contemporary male.

This is not to say that Fincher does not broach the subject of the contemporary male, but his representation comes as caveat. The modern young male is riddled with problematic condescension towards the opposite sex. While Eduardo Saverin is played off as a nice guy, his interactions with women are perhaps overly concerned with exclusivity as a means to get laid (just like the Winklevoss’ Harvard dating website). The moment we find Eduardo at the frat party, standing next to a Dustin Moskovitz whom mentions that he’s finding an algorithm to describe the reason behind Asian girl attraction to Jewish boys, Fincher places these “boys” within a visual reference to John Hughes’ Sixteen Candles.

While this reference allows a context for the film to be read as a coming-of- age picture, the reference then by extension also implies the resolute ending of responsibility acceptance and the eventual maturing of a heterosexual relationship. Instead, what results for these characters is anything but maturity or acceptance of responsibility.

Instead of mature heterosexual relationships, we find women are relegated to game-media in the same way they were once relegated within the kitchen. Within game play there is no responsibility for the decisions that are made via computer programming, coding, or marketing. The young women whom play the games within the film, are then placed into a context of non-integration into this male-dominated industry. Exclusivity returns as a theme that divides the sexes, as all those involved in the Zuckerberg business are male: male coders, male businessmen, and male representatives. Women, are instead allowed to drink a Sex-In-the-City appletini instead of adding to the discussion of business as a partner.

What Eduardo, Dustin, or even Sean Parker do not realize is their light-speed business development has allowed no progress in human relationships, much less any development on the heterosexual home-front that allows women a place like older and more traditional business modes: Gretchen, the older attorney that runs Eduardo’s case, or Marylin Delpy. While Zuckerberg bickers through his intellectual pissing match, revolutionary as it is, Erica Albright is developing into maturity without him. This realization does not occur for Zuckerberg until the moment he asks Marylin to dinner. Marylin’s refusal confirms a divide between two generations. Yet, what separates Marylin and Zuckerberg is not age, nor even success, but maturity. While Zuckerberg may be financially successful, he is reactionary and emotionally unstable to make important life decisions (also a problem for his placement as a CEO), or when confronted with the opposite sex. Marylin, despite being impressed by Zuckerberg, is established and on the verge of becoming a partner in her line of work, but not able to overlook his place as young. It’s no coincidence that Marylin shares a visual similarity to Erin, since it is this clue that provides for an audience mental recall, and perhaps initiates Zuckerberg’s moment of development and maturity at the end of the picture, which we’ll discuss in a moment. First, we must understand that what blocks Zuckerberg’s development is his unquestioned belief in the structure of the society he’s been led to believe is influential and important.

Marylin states that she can make us believe anything if she’s just given the power to suggest, and as mentioned earlier Fincher allows her this privilege, but so to does he convey those of an upper class (those “of means”) also maintain a stance of power merely through suggestion without any fear of confrontation nor refute.

“Don’t you ever apologize to anyone for losing a race like that,” Mr. Winklevoss states to his second-placed twin sons, which at first sounds as a means to comfort for having to not apologize. Yet the father’s decoded message reveals a context of status and class, implying that he is embarrassed and these young men can do their duty to not apologize (and further, not embarrass their family name) again when they no longer lose a race and they work hard enough to remain on top. The Winklevoss twins find themselves constantly reminded of their place in society, their statements and pleas are re- questioned or rephrased by those older, or of a higher class, not in an attempts for resolution, but instead as a means to reprimand. These arrogant rephrasings not only inherently dismiss any oppositional assertions that also remind the other one’s place, but they are continually coded within manners. Every phrase and action of courtesy becomes a potential home for social-threat and insult.

The film’s immediate references towards this arrogance is conveyed within a bar, an environment in which there should be no such class-status, yet Zuckerberg’s initial conversation with Erica Albright approaches this coded condescension accidentally.

Zuckerberg states that he will introduce her to people she’d “be meeting people you wouldn’t normally get to meet,” once he’s admitted into an exclusive fraternity. With the reaction of her offense, the audience takes note about the manner in which every male places themselves in a position of rank or power, be it consciously reinforced through the coded messages of Winklevoss society, or subconsciously as in this pre-break-up moment between Zuckerberg and Erica.

While this coded reinforcement of status is a clear theme throughout the film, the narrative thus utilizes this breakup as an emotionally insightful incident. What takes Zuckerberg the rest of the film to comprehend, Erica states quite flatly when she’s accused of duplicitous statements: I didn’t mean to be cryptic. What is important here is that Erica consciously recognizes that she has hidden pain and offense within sarcasm to briefly hurt and offend Zuckerberg. Erica momentarily plays the game of codes through sarcasm, placing herself above Zuckerberg before she realizes that she’s hurt his feelings and apologizes. Her apology is what allows this moment to hold no further weight upon her shoulders, and allows her the ability to transcend all other characters. No other characters, with the exception of Zuckerberg, come to the conclusion of apology.

So where is the concept that Zuckerberg transcends this moment as immature asshole to convey the recognition of his mistakes? To understand this, we must realize the Zuckerberg communicates most effectively through codes, himself. While this is brilliantly conveyed through the symbolic nature of Zuckerberg’s technical mastery at computer coding, the film also reveals characters comprehending a message from Zuckerberg sent to them via forms of communication other than traditional modes of conversation. Through the coded messages of internet hacking, newspaper coverage, or website creation, the Winklevoss’s comprehend Zuckerberg is giving them the proverbial/virtual finger, so what better mode to apologize for his subconsciously coded arrogance than through the mode that best expresses his attempts to prove he’s sorry and create a website that revolutionarily overthrows class assertions of power and status. His attempts to rectify are thus rendered in an internet power-play. The intention of this plan can be read as assertion to those “of means” that they don’t have the hold upon society in the manner in which they believe to be most true, and the ability to overthrow their influence through the gift of exclusivity to all via a webpage eventually open to everyone. Exclusivity becomes antiquated. This coded message also calls out as apologetic recognition of Zuckerberg for allowing this society’s subconscious influence to over take him momentarily in the bar, and the actions to overthrow this exclusive mentality then becomes his mode of apology to Erica.

This character intention holds the key to understanding Zuckerberg in a way that Marylin’s observations do not. It is critical to understand the human element here, despite the strongly fictionalized addition of Erica or Marylin by Sorkin, since Erica’s response to this statement is offense and breakup results in emotion: panic and sorrow on the part of Zuckerberg. “You would do that for me?” Erica states before she declares he is an asshole, and leaves. Zuckerberg, left to say he’s sorry in monotone that audibly sounds deceptive. Later paralleled with Erica, when Zuckerberg is offered possibilities of inclusion by the elite Winklevoss twins in their plans for their Harvard dating website, Zuckerberg repeats Erica’s words “You would do that for me?” While this moment is most likely the hatching of this previously mentioned revolutionary plan, it also suggests that Zuckerberg is not completely ignorant of Erica’s offended reaction, and he further becomes humanistic through his empathy.

The moments that lie outside Marylin’s evidence-seeking structuring are the attorney negotiations, the few moments in which this real multi-dimensional, emotional, and perhaps more sympathetic Zuckerberg resides. In fact the real motivated emotional outbursts of Zuckerberg come at these moments, such as his threatened and reactionary monologue toward the Winklevoss’ attorney about their taking his “the minimum amount” of attention. While this moment is the heart an aggressive attitude that Marylin’s narrative fully supports, what she doesn’t really convey are the possible emotional ranges Zuckerberg feels that are more in common with those not managing a multi-billion dollar company: human feelings of love, connection, companionship.

Thus we return to the end of the narrative, at a moment in which Marylin no longer has control over the structuring of information, a moment that is amazingly and poignantly captured when Zuckerberg interacts with Facebook in a manner that we’re all familiar: the profile page, rather than any series of Zuckerberg’s pages of coding. This moment is crucial to both a humanist drafting of Zuckerberg’s identity as well as solidifying the unrequited potential for his unrecognized apology.

The sadness of this final closing moment is not that Zuckerberg is autistic, nor an asshole, nor obsessive, but that he has allowed the success of business to fade this retaliation against elitism into the background, and with it the initial impulse for apology. And thus with every click, we await the confirmation of Zuckerberg’s atonement by the fictional Erin, in hopes of the confirming that Marylin’s fractured Zuckerberg portrait is nothing but fiction. Not the negative portrait of a “Kane”-like figure as we initially thought two months ago (years in internet time, I’m sure).

Final Aperture Pro, An Idea for What's to Come

[](http://www.candlerblog.com/wp- content/uploads/2010/11/apreture3promo.jpg)Last week I listed my hopes for early 2011’s iteration of Final Cut Studio. I’ve gotten some great feedback for more additions folks would like, especially on [this thread](http://www.dvinfo.net/forum/area-51/487396-wish-list-2011-final-cut- studio.html) over at DVInfo.net. The two biggest cries seemed to be for 64-bit applications across the board and GPU acceleration, which are both long overdue at this point. However, I’d like to focus just on the unchanged interface of Final Cut Pro for now by looking at Apple’s other major creative app, Aperture.

When Stills Aren’t Still Anymore

Back in 2008, the photography gurus over at The Luminous Landscape posted an article called [Raw Goes to the Movies](http://www.luminous- landscape.com/essays/red-raw.shtml). In it, they lay out the similarities between the Red One camera and digital SLR technology. The key quote comes from a disclaimer at the head of the piece:

There are significant implications for the still photography industry in the RED One and its kin, so if some insights into the future of our industry is of interest, read on.

After the RED One came the Nikon D90, followed by the much-lauded Canon 5D Mark II. Now, you can’t make a DSLR without adding HD video. And so we have two kinds of artists, photographers and filmmakers, converging on the same products. I know folks who rarely shoot video with their SLRs and some who rarely shoot stills. It’s a completely different landscape than it was just a few years ago. Production gear may be moving to meet the needs of filmmakers, but post-production solutions have been slow to follow.

The hardest part of the transition from tape to tapeless has been building post-production software that can keep up with the advances in cameras. When Panasonic introduced their P2 format, most were excited that the hassles of tape would go away. Instead, what we found was that, at least in Final Cut, the digital files still had to be transcoded, a process that took only a bit less time than capturing tapes. Things have only gotten worse as digital formats have proliferated. The files out of Canon’s HDSLRs are compressed H.264s. While they look absolutely stunning, they don’t take as well to color correction as tape formats, they still require transcoding in order to be smoothly edited, and their lack of timecode makes it impossible to match back to your camera “raw” files. At least, that’s the way things are today.

Photo Editing for Film Editors

In Aperture’s parlance, “photo editing” is the process of selecting which photos stay and which will go. “Image editing” is when you get in there and start adjusting colors, curves and anything else you like. I’ll leave it to armchair lexicographers to argue the nominal differences between the terms.

Filmmaking is an extremely old school game, mired in a century of tradition. Our digital editing platforms are all based around language that comes from cutting film my hand. Clip, Bin, and even Viewer are all terms that relate to physical pieces found in an old editing suite. When we went to cutting tape instead of film, the format may have changed but the process barely did. Tapeless workflows, especially for files coming out of HDSLRs, are radically different.

With Aperture 3, Apple introduced the ability for photographers to ingest all of their video files alongside their photos. Once inside of Aperture, videos can be trimmed, tagged, rated, and placed into HD slideshows. They can also be exported for editing in Final Cut Pro, but this process is a bit more laborious than Apple lets on. Aperture 2 only offered to place any non-photo files into a specified directory outside of the photo library. Now, it treats video as if it were a photo that moves.

Imagine a video library for each Final Cut project that is self-contained, much like the Aperture Library. In it you could tag media, hide clips you don’t like, and update metadata quickly in an interface that mimics Aperture. While you can certainly edit metadata in Final Cut today, the Browser window is cramped. Even when you have a monitor big enough to stretch it out, it’s tough to get anywhere without a right click. The simplicity of photo editing in Aperture, Adobe’s Lightroom and similar applications is something that could make media organization for video editors a breeze.

Final Aperture Pro, The Perfect Final Cut 8?

Aperture 3 is 64-bit, exists within one unified window and sports a slick full-screen interface, three features that make it the perfect pro app for Mac OS X 10.7 Lion. As I pointed out in [my Final Cut Studio wish list](http://www.candlerblog.com/2010/11/12/a-wish-list-for-the-2011-final- cut-studio/), Final Cut’s interface is still based around a Mac OS 9 design. Whether we like it or not, the overall interface is do for an overhaul and I have a feeling it’s going to, eventually, start looking a lot like Aperture 3.

When I bring this up to other working editors, the biggest fear is that they would have to re-learn how to use Final Cut Pro. Most admit that the interface has its drawbacks, but has ultimately won them over. Changing things drastically would, unquestionably, alienate a lot of users. A few counterpoints to that though:

- You don’t have to upgrade. 2. You should never upgrade in the middle of a project, ever, on any platform. 3. Change for the sake of change is bad, but iterative interface upgrades aren’t inherently bad. 4. You can learn new software; [don’t panic](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don%27t_Panic_(The_Hitchh iker%27s_Guide_to_the_Galaxy)#Don.27t_Panic).

Apple, I hope, learned their lesson about drastically changing their interfaces after they introduced iMovie ’08. They are not a company that makes the same mistake twice, so don’t expect Final Cut 8 to be identical to Aperture 3. I’m betting it will still look very similar to the same ol’ Final Cut interface, but hopefully in one unified window that can make use of full screen real-estate. The biggest update I’d like to see is a browser that looks a lot more like Aperture, while keeping the actual tools of cutting the same (or similar).

What Aperture does well is keep projects organized under one roof. Final Cut is still based around a folder/bin structure that is up to the editor to maintain. There are times when “Smart Folers”, organized on the fly by metadata, would come in extremely handy in Final Cut. Photographers have the luxury of software that is built to bring in all of their creative output, whether it ends up being worth keeping around or not. Video editors, on the other hand, can lose control very quickly when piles of media get sucked into a bloated Final Cut project.

Documentaries for example have far more unused footage than fiction films simply by the nature of how shooting one works. In an Aperture-like version of Final Cut Pro, the documentarian can throw all of the footage he or she has into a Final Cut project and begin tagging and/or rating the various takes. Some films take years to shoot. With Final Cut as it stands now, it can be an insurmountable task to organize all of that footage. In fact, it may be easier to keep it organized outside of Final Cut. With a more robust organization system, this process could become much simpler to handle.

A system like this could also, theoretically, cut out the lengthy transcoding process filmmakers go through that leaves them with (at least) two sets of media. I’d love to see a version of Final Cut that treats camera originals of HDSLR video the same way it now treats RAW stills, in which the original files are always accessible beneath whatever “version” is currently in use. This could, potentially, subvert the need for real timecode on DSLRs, because your camera originals would be linked by file name. It’s not a perfect solution, but one that could work better that we have right now.

I don’t doubt that when Apple introduced iMovie ’08’s much-maligned interface, their intention was to judge how users took to it in hopes of making it the future of their video editing applications. Some of that interface has made it into Aperture 3’s design. The slideshow editor feels lifted straight out of iMovie. The more I look at Aperture 3, the more I hope that Final Cut Pro 8 looks more like it than FCP 1.2.5. At the very least, it would be nice for the two applications to have better integration so videos organized in Aperture could be easily worked with in Final Cut. Given how related our SLRs and our video cameras are these days, this seems to be an inevitability.

Lossy Hype, Or Wishing for Files Bigger Than Jesus

Yesterday, Apple put a bombastic splash screen up on their webpage, promising today would be a day we would never forget. The web exploded with buzz about major changes coming to iTunes, though by the evening it became clear that the impending announcement was the introduction of the Beatles’ catalogue to the iTunes Store. Early this morning, that turned out to be true, the prolific rock group’s entire oeuvre showed up sporting special features galore. It’s a good looking collection, but was it worth hijacking the front page of the world’s largest music reseller for 24 hours?

First of all, it’s important to understand the history of Apple’s relationship with the Beatles. All of the Beatles albums are owned by Apple Corp., a company that predates Apple (née Computer) Inc. by about a decade. The two have sparred in court for decades, most recently after Apple entered the music business with the introduction of the iPod. The “Beatles on iTunes” story has been floating around the tech world for years, and is probably the last of the major Apple rumors of the last decade (the tablet and the phone/PDA being the others). That it has been put to rest is a big deal given the contentious history.

Apple now serves up 256 kbps (kilobits per second) AAC files to its many listeners. Most people aren’t audiophiles, not to mention the fact that most don’t even have the equipment to tell the difference between bitrates. Still, there is something to be said for lower compression, higher quality formats, like Apple Lossless, which is basically a high bitrate AAC file. The biggest problem with any compressed file is that you can’t fill in the missing bits later. With a CD (also digital, but with very little compression), when you have enough storage to up your bitrate from 256 to 320, it’s only a matter of re-ripping the disc. I had hoped that Apple’s big announcement today was going to be the introduction of Beatles content for purchase as Apple Lossless files, with other artists to follow.

Compression is a tricky business, especially considering that formats, wrappers, and encoders will come and go throughout the course of history. Who knows if we’ll still be able to play AAC files in the future, or if we’ll even want to? All I know is that I’m much happier having The Beatles’ albums as Apple Lossless on my hard drive, ripped from the CDs which I keep safely tucked away. They sound wonderful.

A final thought: iTunes originally sold 128 kbps audio for their entire store until they changed everything over to 256 kbps last year. When files doubled in quality, Apple offered purchasers the ability to upgrade to the newer, better format at a discounted rate. It’s an interesting model, and one consumers should get used to in a climate where formats will continue to change. That being said, if one had bought the CD in the first place, one wouldn’t have to worry about paying for anything again.

Review: Unstoppable

I won’t mince words: Tony Scott’s Unstoppable is one of the best directorial efforts to come out of Hollywood this year. Technically masterful, emotionally even-handed and physically weighty, it is the most accessible of Scott’s recent deconstructions of the American condition. Even better, the action sequences stand two heads above anything else made this year.

On his fifth outing with Scott, Denzel Washington plays Frank Barnes, an aging motorman working towards retirement. Will Colson, played with fluent charisma by Chris Pine, is a rookie conductor going out for his first day on the tracks with Barnes as mentor. The relationship is rough from the get-go. Colson is related to management and works for far less money than those of Barnes’s generation. He represents the new class pushing out the old, and Barnes never lets him forget it.

Elsewhere, a bumbling driver named Dewey, played by sad sack Ethan Suplee, accidentally loses control of a half-mile long train with hazardous chemicals in tow. The series of events that lead to this happening are too confusing to list here, but it should be noted that they are completely believable and, more alarmingly, probable. The film, after all, is inspired by true events.

The brilliance of Unstoppable is that the conflict, the speeding train, lacks a human antagonist. Human error is the cause, a force that weighs heavily on Dewey throughout the film. There are no terrorists whose motivations we need question, no obstacles of evil to resist. There is, however, a bad guy. His name is Galvin (Kevin Dunn), the head of the rail company who is concerned only with the bottom line, not the toll on human life the train could cause. Through him, we see the evils of capitalism. A room full of smarmy executives decide the fates of whole cities based solely on stock prices. The class struggle between Colson and Barnes is obliterated by Galvin’s greed.

It really isn’t until the last third of the film that Colson and Barnes begin to chase the runaway train. Before that, a spectacular plan is put in place to slow the train down and drop an ex-marine onto it from a helicopter. The sequence is pitch perfect, not only for its spectacle but for the seriousness with which it handles human vulnerability. The danger is extremely real, and as things go awry (as they are wont to do), the audience is able to feel the pain alongside everyone on screen. In a world of PG-13 action films, cartoon violence seems to prevail. Here, when a person falls down for good, it rips you apart. Unstoppable nabbed a PG-13 rating, proving you can make action that hurts and get it past the MPAA.

Huge kudos to Chris Lebenzon and Robert Duffy who edited the piece. It’s not easy to get the right kind of tension with as much camera movement as Scott uses, but they were remarkably up to the challenge. The film has its quiet moments which pull us to the edge of our seats, and the final leg of the pursuit is a stunning bit of old-school action. In general, rail action is something of a throwback. There is a blatant message of blue-collar workmanship, and the men and women (I should mention Rosario Dawson holds things down on the mic as yardmaster Connie Hooper) who keep rail travel running feel as ancient as the tracks on which they drive. Of course, when a train goes out of control, all the MBAs in the world couldn’t save us from ourselves.

Tony Scott may be the closest thing we have to a backlot director. He works hard, he works fast, and his films are successful enough (extremely successful, actually) to allow him to make the films he wants. He wields a massive, captive audience and his films have long been parables for the current American landscape. Sometimes, it takes a foreigner to expose who we are. Whatever it is that Scott has to say about us, his technique and his message have never matched up as beautifully as in Unstoppable.

[](http://www.candlerblog.com/wp- content/uploads/2010/11/unstoppable-publicity-still.jpg)

A Wish List for the 2011 Final Cut Studio

Pro Apps on Lion

It gets worse if you look at where Apple’s Pro Apps, specifically Final Cut Studio, have been all this time. Don’t get me wrong, Final Cut overall has seen plenty of advances over the years, and it is still the editing choice of a growing number of filmmakers. However, there are major stumbling blocks that hold it back from being the perfect post production tool. Recently, a user e-mailed Steve Jobs asking for a Final Cut roadmap, receiving in return assurance that an update is coming “early next year”. Here is my wish list for what I believe would be most useful for creative professionals.

Unified Interface

One thing that Final Cut Studio’s developers have been scared to change, and rightfully so, is the overall interface of the editing program. The proof that this is ground worth treading softly on is in the release of iMovie ’08, which stripped down the consumer software’s interface to the bare minimum. Relying more on clips smashed up against one another than on a “timeline” metaphor, Apple alienated tons of users who couldn’t grasp the change from previous versions of the software. In ensuing releases, they have slowly added the lost features back. However, the damage was done, and you can’t reinvent the wheel overnight for software that powers an industry. But how stagnant has Final Cut’s interface been?

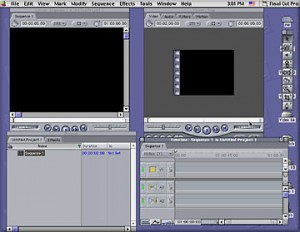

Final Cut Pro 1.2.5 Screenshot

What does it mean to say that Final Cut Pro 7 is a modern, powerful application stuck in an OS 9 body? For starters, Final Cut relies heavily on multiple windows floating over the desktop. Get rid of any window and you can see the desktop behind it. Oddly, even the “standard” Final Cut display will leave a little bit of the desktop peeking out (in the lower right corner of the screen). This has long been a Mac-ish concept, so much so that when Adobe opted to introduce a more Windows-like neutral background in Photoshop CS3, users sparred a bit over the de-Mac-ification of the application. As Adobe’s John Nack pointed out back in 2008, Apple’s own applications have a bit of schizophrenia when it comes to interface:

{% blockquote %} What about Apple’s own applications, as they would be presumably be the definition of Mac-like, right? I noticed a couple of things:

- The pro video apps (Final Cut Pro, Motion, Color, DVD Studio Pro) configure their windows/panels to take over one’s screen completely.

- Aperture and iPhoto put all the UI into a window & optionally take over the screen in a dedicated full-screen mode.

- The iLife and iWork apps (Keynote, Pages, iWeb) all feature a UI approach that marries together content & interface in a single window. {% endblockquote %}

Here are a few additions to his list (all of which stands true after two and a half years):

- Soundtrack Pro and Motion take up one whole window with tabbed toolbars that can be “torn” off into new windows/panels.

- DVD Studio Pro mostly consists of one big window with the same tabbed toolbar interface, though out of the box it also has extra panels which are their own windows.

- Color is really an island unto itself; it fills the screen completely in one big window with a much different interface based around “rooms”.

- Compressor is a mess; it bunches panels together slapdash. Even simple transcoding tasks become a hassle because you have to deal with so many windows. The same goes for Cinema Tools, which has far too many windows for a simple database application. Basically, everything needs an overhaul, and we can only hope that’s what’s been taking them so long to deploy a fully updated evolution of the Final Cut Studio suite. I don’t know what it should look like, but it probably won’t look anything like iMovie. I doubt the trusty “sequence” is going anywhere, but given the major changes Lion is bringing, I wouldn’t be surprised if we start to see a new fullscreen interface with a streamlined window configuration.

What’s that? You say that Apple has consistently updated Final Cut Studio every year or so? Wrong. Which brings me too…

[Media] Studio Pro 5, Please

Sad DVD Studio Pro

So what gives? No Mac ships with a Blu-Ray drive, which was presumably the holdup during the “format war” with HD-DVD in 2007. Apple wasn’t ready to throw its weight behind either format, instead waiting to see who would win, but Blu-Ray soundly won that battle in 2008 yet Apple still hasn’t shipped any high-capacity optical drives. The newest Final Cut Studio allows users to burn Blu-Ray discs, but not to design them with the ease and comprehensiveness of DVD Studio Pro. Instead, customizable menus require a good deal of coding, and even then the control scheme is lackluster. The only product on the market that allows you to author Blu-Ray discs with any kind of creativity is Adobe’s Encore, which doesn’t play too nice with Apple’s Final Cut codecs.

It gets worse. Physical media will be around for a long time as a distribution pipe (if I had to guess, I’d say at least a decade, if not two), but the writing is on the wall: downloadable media is the way of the future. Apple knows this better than anyone, given the revolutionary stance iTunes has taken on the matter. Last year, Apple introduced iTunes LP and iTunes Extra added features for music and movies on the iTunes Store, respectively. These functions basically feel like the interface of a DVD menu, except they exist only within the the user’s music/movie download on his or her computer. If the entire DVD experience is going to be digital, without physical media, will Apple be able to deliver an application to creative professionals? Right now, you have to be a coder to get anything done with these features. (Don’t get me started on creating slick HTML5 apps for the Boxee Box and GoogleTV; the same argument applies.) Hopefully [Media] Studio Pro 5 will help us deliver content wherever the eyeballs (and, yes, checkbooks) are.1

Put the App Store to Good Use

While it may not seem feasible to deliver Final Cut Studio through the forthcoming Mac App Store given its gigabyte girth, there is always room for third party enhancement via instant downloads. Final Cut has an active plugin community, and it would be great if all of those plugins could be managed through the App Store. It’s currently unclear whether the App Store will be able to be used for plugins, but it could be one day.

Imagine you could access a plugin App Store from within Final Cut. You come across a problem in need of a solution; you would immediately be able to browse through options for your specific need. Many companies offer plugin packs to cover the cost of delivering the software to users. With a plugin App Store, instead of 50 plugins for $100, 49 of which never get used, users could drop $2-$5 a pop for exactly what they need. Better still, when enhancements to a given plugin come in the form of an update, simply run all of the updates from Final Cut. The same goes for Motion textures, DVD Studio Pro templates, or Compressor presets. The market would be massive. Time will tell if Apple wants to allow the Pro Apps to play in the App Store.

Refine the Menial

Editing, like all creative pursuits, is an action of the mind. Great editors can find the perfect way to bump a series of pictures up against one another in order to convey an intellectual or emotional concept. As my junior high school music teacher told me when I said my saxophone was a piece of crap, “If John Coltrane walked in here right now and picked up that sax, he’d still be John Coltrane.” Tools don’t make art. That being said, there are a ton of niggling tasks that are a part of any post workflow, and Final Cut makes them a nightmare sometimes.

Clients (unlike artists) don’t want to know the inner workings of editing software. They just want their stuff. Here’s a list of things that will make it easier for all of us to get things done faster and, more importantly, right on the first try:

- Better frame accuracy when running up, down and cross-conversions via the AJA-KONA, including the ability to change the offset by a half frame for 60p-to-30i outputs.

- In line with the above, Deck Control schemes tailored to actual decks, not just Manufacturer+Frame Rate. (I have never had a problem with frame accuracy on Avid; not once.)

- Timecode display during capture and output of any media. I want to see it from across the room while I sip my Double Gulp.

- More intuitive audio output configurations, please. It’s a pain to “right-click in the gray space to the left of the sequence but before you hit the green ball” and even worse to say that over the phone to a client who has to deliver an 8-track Quicktime.

- Better Media Management. I’ve never seen a project completely come over to a new hard drive with render files. Never.

- Deliver on Final Cut Server’s promise.

- Fix Compressor. We should be able to export multiple clips in multiple formats to multiple directories without ctrl-clicking until our fingers fall off. Also, the interface is still way too confusing.

- Put Color in Final Cut where it belongs. While the picture-lock-to-color-correct workflow makes plenty of sense, it’s a holdover from tape-based workflows. Creatives shouldn’t have to choose if they are going to color now or later.

Roll Out

Everyone has a different use case for Final Cut Pro, and no two workflows look alike. If Final Cut changed anything in the post production game, it made it easier for those who have no workflow whatsoever to jump in and start making movies, more than any other piece of editing software before it or since. The digital revolution needs software that gets out of the way and allows filmmakers to explore their wildest creative thoughts. Many of my requests fit my workflow, but I’m one in a million. Nonetheless, I think this wish list is a decent start. I’d love to hear what the rest of you would like to see in Final Cut’s next release in the comments.

-

I should note that this notion was first put into my head my head by listening to Alex Lindsay on MacBreak Weekly. ↩︎

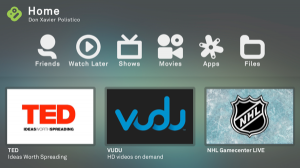

Boxee Box Launches in NYC, Promises to Bring Tons of Video to the Living Room

When Avner Ronen took the stage at Irving Plaza last night, he was met with whoops and hollers, requests to break into dance (to which he eventually acquiesced) and the clanking of PBR tall boys. He is not your average CEO. The setting for the launch of the aptly named Boxee Box, was perfect for a company as scrappy and ideologically cocksure as Boxee.

In a mere three years, the Tel Aviv and New York based startup has batted down nearly every one of its software competitors only to enter a hardware arms race against Apple and Google. Ronen has become something of a web video evangelist, famously sparring online with mogul Mark Cuban over the future of television. Now, he’s taking his company from the original free, hackable app that turns any computer into a net-centric media player with a slick interface, to store shelves in time for the holiday season. The product of a partnership with D-Link, the Boxee Box is here and the software is finally out of beta.

But what’s the big deal?

The Boxee Box brings what was once a very nerdy experience to the masses. Installing Boxee may never have been that hard, but hooking your computer up to your television, along with the audio, and figuring out how to control it from your couch was where the less tech-savvy stumbled. Now, it’s as easy as plugging in the box.

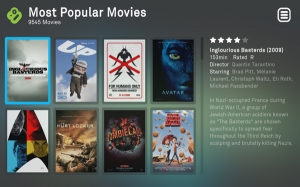

What sets the Boxee Box apart from its competitors is its ability to playback non-streaming media in almost every single format imaginable. As Ronen quipped, “If it has 3 letters in its name, we can play it.” With two USB ports on the back, users can attach massive storage for all of their videos and music. He played a 1080p x264 video off of an SD Card and it looked beautiful. Details are a bit thin right now, but Ronen did mention from the stage that users will be able to share that storage with other computers via Wifi.

Then there are the big partners, Netflix and Hulu. These announcements Avner coyly saved for the end of his presentation. Netflix, who has been a longtime partner with Boxee, will be coming later this year to the Boxee Box with a completely revamped interface and HD streaming. It appears that right now, users with a Boxee Box can still access the old Netflix app, but not in HD, yet. Hulu, who has a contentious history with Boxee, is bringing their paid Hulu Plus service sometime early next year. “It’s true, we’re friends now,” Avner fawned, “Next up, Middle East Peace.”

All of that aside, and it’s a lot to set aside, the most interesting part about this product launch has nothing to do with their partners or their content on day one, but with their pragmatic view of web video and how it fits into the living room. The Boxee Box now has a brand new Webkit browser built in conjunction with Intel (who provides the system- on-a-chip inside). If you want, you can view an entire webpage with video playing on it, using the remote’s directional-pad to push a mouse pointer across the screen to get what you need. The thing is, Avner sounded downright sour that a browser is accessible through the Boxee Box. “It works, it’s not pretty, but it’s there if you need it.”

That’s not all he had to say. “Browser on a TV kind of sucks.” This sounds like a direct shot at GoogleTV, whose demo showed off how much browser they could fit onto a television. So if the browser concept sucks, what about apps? “Idea of apps kind of sucks.” It’s not that apps on your TV is a bad idea (especially since Boxee basically relies on them), it’s that there are too many APIs and Development Kits and platforms out there already; Boxee doesn’t want to become another language for developers to learn.

The workaround? HTML5. Ronen explained that developers can build some really cool HTML5 video apps which the Boxee Box will be able to access. He demoed a New York Times app that looked great; no one would ever question its code provenance. Given that HTML is an open standard, this makes it easier for developers to get in line. GoogleTV supports HTML5 apps as well, so it will be easier for content creators and channels to develop once and deploy to both platforms. The AppleTV does not do this, but Avner said he hopes they’ll start soon so that content creators can be on any television.

The Boxee Box is a very nice offering for consumers, and it is priced competitively to move a lot of units this holiday season. At $199 it’s twice the price of an AppleTV and $100 less than the Logitech Revue, GoogleTV’s flagship device. The thing it, it does (at least) twice as much as the Apple TV and probably more than the Logitech Revue. For content creators, this means yet another barrier has been broken down. To get your content onto Boxee is only slightly more difficult than getting a podcast into iTunes. The more homes with a Boxee Box, the more eyeballs for content creators to reach.

I didn’t get the chance to actually use a Boxee Box (though I’m told I’ll have the opportunity soon) so I can’t speak to its actual quality. I’ve been using the software since it was in alpha, and if you told me three years down the line they’d be in retail stores up against Apple and Google, I would have said you were nuts. Yet here we are. It could very well be a flop. However, if you’re a content creator looking for a new way to reach audiences, there has never been a better time to get your media into the homes of the masses. Whatever poison you pick, the Boxee Box appears to be another great option in a year that looks poised to be a hallmark one for streaming video.

3D's Viability Depends on Indie Adoption

[](http://www.candlerblog.com/wp- content/uploads/2010/11/EnterTheVoidStill.jpg)Last week, esteemed film writers Anne Thompson, Leonard Maltin and Eric Kohn [posted the transcript](http://blog.moviefone.com/2010/11/05/three-critics-anne-thompson- leonard-maltin-eric-kohn-3d/) of a conversation in which the trio discuss the relevance, artistry and bankability of 3D cinema. It’s definitely worth a read, especially given the unique perspectives of Thompson as industry insider, Maltin as historian and Kohn as cinephile (I’m oversimplifying, each one fills all of those roles at varying points, but the transcript makes it clear whose strengths lie where.) I’d like to throw my opinion into the mix on the subject of 3D as it stands today.[pullquote]

3D, like any other visual technology, is only as good as its output.

[/pullquote]

Most of their conversation is well-trodden ground, the predictable tropes we’ve been hearing all year. Maltin opens “3-D alone isn’t enough anymore. We’ve had several 3-D flops. Take Clash of the Titans. Say you’re at Warner Bros. and you have, on the one hand, a guy saying, ‘This 3-D quality sucks,’ but then another says, ‘Yes, but look at how much money we made this weekend with it anyway.’” The accepted wisdom is that 3D is a gimmick that exists only to squeeze extra pennies out of movie-goers. True, but not really true.

3D, like any other visual technology, is only as good as its output. A movie camera is no good without someone to work it, preferably someone with a vision of how to advance cinema. Whatever you think about Avatar, James Cameron is that person, he is the artist who has the drive and determination to see 3D flourish as a legitimate art form not just today, but for its next century. The film isn’t a talking point because it found a new way to press audiences for revenue, it’s a part of history because when we look at the timeline of cinema, we can point to the 2009 release of Avatar and say “something changed here”.

But, and this is a big but, James Cameron is not the artist who will break down the barriers between Big Hollywood and indie visionaries. As much of a technological wiz as he is, his evangelism goes only so far as the most basic, plastic issues of filmmaking. What we need is someone who can take the technology, take the buzz and wrangle it into a viable artistic movement. We need someone to save 3D from being destroyed by the Hollywood money machine.

I have heard chatter that Gaspar Noe wanted to make his psychedelic Enter the Void in 3D, a pronouncement that sounds like a self-serving bit of braggadocio. (It also elicits giggles from the peanut gallery given the film’s literal climax.) Wracking my brain, I couldn’t think of a film that could have done more for the format than Void. The camera bobs, weaves, floats and devolves into light-soaked wormholes, spindly arms reaching out to the audience and taking hold. As an experience, it is wildly immersive. For some, it may be unwatchable, but the folks who can make it through all the way and laud it are exactly the sort of people who need to be jolted into 3D acceptance.

Finally, I would like to address the argument that 3D is a gimmick. It should be noted that the same argument was made for CGI, CinemaScope, color film, sync sound and cinema itself in each of their respective infancies. We grow and we learn over time. It is an offensive, classist argument akin to “animation is only for kids”. No crossover filmmaker has yet come along to embrace 3D strongly enough to make it artistically interesting, but give it time to grow. 3D will only be here to stay if the indie, arthouse community embraces it. Time to wait and see.

NYFF '10 Recap: Robinson, Socialism and My Joy

[](http://www.candlerblog.com /wp-content/uploads/2010/10/cannesjoy718.jpg)Film festival coverage is never easy, especially when for 4 weeks, as is the case for the New York Film Festival, critics and journos meet daily to view films that will be screened to the public as soon as a few days away, as little as a few hours later. The task is, to say the least, daunting. Which is why I have barely covered anything from the fest. Now that I’ve thoroughly digested my viewing (about a dozen films) I can share a few thoughts about them with you. This first batch is for films that fell outside of my normal viewing habits. It’s a cop-out to say these are films I didn’t “get”. It would be more accurate to say they just didn’t jibe with my tastes, but I have an obligation to share with you what I mean by that. So this first group could be called “Stuff you Will Probably Never See, but Wouldn’t Mind Reading About”. Without further ado:

Robinson in Ruins

Cinema’s powers are so diverse that perhaps we forget it can be used in

academic discourse outside of the realm of fiction, documentary and industrial

work. Robinson in Ruins is an essay film by Patrick Keiller with a simple

premise. The footage you are looking at and the long running narration are the

work and notes of one Robinson which was found near a trash can. The film is

the assumed result of his work in his absence.

The film is a lengthy diatribe on the history of capitalism, it’s reshaping of earthly pleasures and, err, the changing spatial layout of environs. The camera never moves, instead always facing forward at the world it is examining. Analyses and parables are read to us by Vanessa Redgrave whose soothing, disembodied narration makes the placid imagery far more palatable. The words are dense and the ideas are high-minded; I would love to read the entire narration in pamphlet form. Which brings us to the fundamental challenge of a work like this: keeping the viewer visually engaged while the brain is being stimulated in so many other places.

There is a reason why the printed page still exists; there is a reason why we invented the highlighter, for linear and deconstruct-able learning. Which isn’t to say Keiller’s film isn’t a valid way to access and stimulate various receptors. On the contrary, it has the ability to suck you in, aggravate and stir up nearly all of your mental faculties. Younger, more malleable minds, perhaps, would benefit from this method the most. It is a beautiful and endearing use of cinema, even if it is one my solidified mind has trouble letting in. What is the film “about”? I couldn’t tell you if I tried (and I think I just did).

Film Socialisme

Ah, Jean-Luc Godard, where can I even begin? Challenging is a word that I will

use to describe the director’s last few films, and I don’t intend that to mean

“incomprehensible”. More a sense of bravado, a line being drawn in the sand,

an outright playground after school while your buddies whoop you on kind of

challenge; a duel, a battle. Will you take him on, take him down, call him on

his bullshit and recognize his artistry? I, for one, will not. It’s a cop-out,

I agree.

Film Socialisme centers around characters on a boat who speak various languages, mostly the director’s native French. For the English release of the film, Godard dictated that the subtitles be translated in part, not in full, resulting in what the director calls Navajo subtitles. Words are omitted, most nouns get to stick around, and modifiers smash up against each other. In short, Anglophones and Francophones are seeing two different films. Or are they? I never felt lost on account of the stylized text. My limited French kicked in and noticed the difference between what was said and what was written, and got the point of the dialogue anyway. Perhaps the French speakers are missing out.

Where one can easily get lost is in the film’s content. The ramblings of undeveloped characters, people whose relationships and essence are never explored, are the film’s entire makeup. It can be tough to follow what is happening, where we are and why, but not so hard. You just need to work at it. That is common for post-Dziga-Vertov Godard. Also common in his work, and more of a sticking point for me, is anti-semitism. Godard’s vitriol is mostly reserved for Israel, making his anti-Jewish flourishes more innocuous and socially acceptable (he is an avowed anti-Zionist). Is it anti-Semitic to criticize Israel? It depends, and it’s tough tell with Godard. At some point the denial of a Jewish homeland has to be squared with how you feel about the Jewish people, but so long as there is a perceived debate over whether Jews are a people or a religion (we’re a people, there’s no debate) this is a question that will probably go unanswered in the arts community. What is less nebulous is his pointing out of Hollywood, long the creative enemy of his cinema, as a Jewish machination, a Protocols of the Elders of Burbank of sorts. He brings it up briefly, unmotivated enough to barely give us pause. Is Godard anti-Semitic? That discussion will continue for decades.

****If we separate his cinema from his politics, something that undermines his essence and intent, what are we left with? As always, a brilliant exercise in form. The Godard of the 1960s, the one many refuse to let go of, explored form alongside his Nouvelle Vauge colleagues, within the confines of narrative, until eventually he broke off and explored form for it’s own sake. After all these years, he continues to prove that cinema, both visually and aurally, corporeally and plastically, is a space barely excavated. He still possesses a childlike curiosity, digging his fingers in the mud just to see what comes up. It may only be worms, but that he rooted around in the first place is what sets him apart. (That metaphor doesn’t hold so much water, I realize, since Godard knows exactly what he is doing. Still, there is a childlike sense of discovery in his work.)

My Joy

And finally, a film I not only understood (to the best of my non-Eastern Bloc

capabilities) but outright hated. My Joy is the sort of film you expect to

see at a cynical, upper crust, hoity-toitety film festival. In other words, it

is exactly the kind of film that has given the New York Film Festival its

reputation as a pinky-in-the-air, self-ingratiating film education given from

on high. (I’d like to note that I don’t agree with this viewpoint, but it’s

out there and it’s something the NYFF lives with and, frankly, revels in. Who

wouldn’t want to be called “too smart”?) Director Serhiy Loznytsya could have

gotten to the point much faster by saying “Russia is an unforgiving, shitty

place,” but instead we sit through this film that jumps through time,

characters and motivation.

To say that it is a dreary film doesn’t even begin to describe it. Families are murdered, the downtrodden get downtroddener and plot lines come and go at the drop of an ushanka. We follow Georgi, a charismatic truck driver with a few secrets behind his eyes, through the depressed economy of his nation. He picks up a hitchhiker, tries to save prostitute from a life on the street, and gets ambushed by countryside bums. It is not a good couple of days.

It’s no secret that this film has a clear message about where Russia finds itself in the world today, but that is part, if not, all, of the problem. It’s “message, message, message” not “story, story, story”. I don’t care, but not because I am heartless; because I am not made to care. If this is a parable, we should be getting story first. And form? Not impressive enough to overcome the narrative missteps within this film. Perhaps if I were Russian, perhaps if I had a horse in this race, I would think it a brilliant deconstruction of a culture. But I’m not, and so I’ve got nothing.

NYFF '10 Review: Hereafter

[](http://www.candlerblog.com/wp- content/uploads/2010/10/hereafter-movie.jpg)Hereafter is Clint Eastwood’s latest soapbox, proving that the octogenarian director has neither lost his flare for the dramatic nor his moralistic pulpit. In the film’s opening moments, he provides perhaps his most technically resplendent sequence, executing a massive natural disaster, a tsunami, with a camera that whips and winds with the current of an overflowing sea. Yet from that point on, the curmudgeonly Eastwood we have come to know in the past decade drags out a boring tale of love, loss and the afterlife. It is, to say the least, a snooze.

Taking advantage of one of the easiest ways of duping an audience into thinking they are watching a tale of emotional discovery, Hereafter relies on intertwining, seemingly unrelated plot lines. There are three in this film. George Lonegan (Matt Damon) is a San Francisco based psychic trying to lay low after a successful run as a supernatural healer. Marie LeLay (Cécile De France) is a Parisian news anchor (and Blackberry spokeswoman) whose extreme brush with death leads her to put her career on hold. Finally, Marcus and Jason (Frankie and George McLaren) are precocious twins who try to keep their deadbeat mother in shape lest they be swept off by child services. The trick is to keep the plot moving forward in each story line, usually at the expense of character development. The trouble is that no one plot stands out above the rest, and their collision at the end is completely nonsensical.

Viewers may not be surprised to learn that Steven Spielberg played the role of Executive Producer on this film. Given his penchant for dabbling in projects under his purview, I wouldn’t be surprised if the aforementioned opening sequence didn’t have at least a little bit of his direction. As the tsunami breaks through an entire civilization, our perspective remains steady, changing only as emotionally necessary. Given the scope of the destruction, it sounds simpler than it actually is to pull this off. It is a powerhouse sequence, that is until a teddy bear turns into some kind of god-like talisman. Ironically, this is when it turns into a disaster film.

Hereafter also hinges on a very Spielbergian concept: heartache. Given that we know this is a story dealing with life after death, Eastwood immediately plays on our emotions. He lets us know that someone, if not everyone, will die before our eyes, but not before we gain an emotional connection to them. Those who have vilified Spielberg for this in the past will go on the attack if only for the excruciating introduction of Marcus and Jason, whose dreary lives are almost sure to end in horror. To make matters worse, for all the shoes that could have dropped on these people, for all the monsters lurking in closets, the one we end up with is eminently banal.

I’m not going to talk about performances; they’re all serviceable but none are stellar. Now it’s time to turn attention to perhaps the most surprising misstepper in this hard-to-love film: Peter Morgan. One of Britain’s top A-listers, it’s hard to believe that the drivel on screen came from his gifted pen. His fatal mistake is that the afterlife is dealt with as both a religious and a scientific reality. He doesn’t go to any lengths to defend either viewpoint. For example, a “scientist and atheist” in the film provides incontrovertible evidence that there is in fact life after death, but we are never allowed to look at that evidence. Moreover, we are never given the boundaries of this world of the dead. Instead, it remains unknown and uninteresting throughout. This kind of film requires the grounding of Science Fiction, a suspension of disbelief that is entirely unemotional. Morgan did not provide.

Ultimately, Hereafter falls flat for its weak story. Clint Eastwood remains an icon and a talented, steady director. When George takes on a client of his brother’s (Richard Kind as the client, Jay Mohr as his brother) the scene is dark, quiet and moody. He plays in the dark and can build a beautiful scene out of the thinnest of dialogue. In the end, however, it isn’t enough to overcome a story that will have you unintentionally rolling on the floor by the overwrought ending. “Is this for real?” was my internal monologue as the music crescendoed and credits took over. Alarmingly, yes, it is.

Candlercast #18: A Full Scale Chat with Jeff Malmberg

Jeff Malmberg and Mark Hogancamp of Marwencol

If you haven’t heard of the film Marwencol yet, it’s time to perk up. You can read my review from this year’s SXSW to become fully acclimated. The documentary, which follows Mark Hogancamp and his 1/6th scale Belgian village whose name is the same as the film, has been winding its way through the festival circuit all year and is finally ready for its theatrical debut. It opens today in New York City, and with it came director Jeff Malmberg.

Marwencol marks Jeff’s directorial debut. He was worked as an editor for a number of years, but it wasn’t until he started cutting documentaries that he found his true calling. He took some time out of his schedule to sit and chat with me about the film and his burgeoning career. More than anything, it seems, Jeff loves to talk about Mark, the star of his film. Don’t take my work for it though. Click on through and listen to Jeff’s story. He talks about how he came to make this film, the state of documentary today, and why he chose a narrative structure for Marwencol that some others may have shied away from.

{::nomarkdown} Sorry, your browser does not support the audio element. {:/nomarkdown}

[Right-Click to Download](/images/2010/10/candlercast-18 -jeff-malmberg.mp3) • Subscribe in iTunes

For more information about Marwencol and release dates, please visit the official site.