Introducing Watch This, A New Weekly Column ⇒

The team over at Turnstyle just launched a new weekly column over at Turnstyle (where I also wrote a bit of coverage from SXSW) featuring the writing of yours truly called “Watch This.” Every week I’m going to feature and critique a film I find on the Web. From the first post, which went up a few hours ago:

Art, of any discipline, can only be as strong as its criticism. Critics are usually remembered for their harshest writings, but it is often the most critical writings that contribute to the unending conversation about cinema. Is it even possible to think about the rise of New Hollywood without the writings of Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris? Critics can boost the profile of unknown work, enhance the global discussion of cinema and in some cases challenge filmmakers to make more complex films.

With that in mind, I have found that Web video, on the whole, is lacking in serious widespread criticism. Yes, online filmmakers have their champions, but there is such a glut of content uploaded every day that the critical community can barely keep up. Dated as it may be, the weekly theatrical release paradigm has allowed criticism to flourish alongside it. My goal is to sift through Web videos and, once a week, share with you a film that catches my eye and deserves some close inspection. Hopefully, this space will be a weekly snapshot of what is happening in the online film community.

I’m excited to see how this project goes.

Where Tech, Celebrities and Washington Meet ⇒

Excellent reporting by David Carr from the New York Times on the significance of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. He paints a picture of the technology industry throwing its weight around in Washington as the “new” celebrities on the hill.

Carr opens the piece with an anecdote about Judd Apatow meeting Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman and former CEO:

“Wow, I had to do a double take when I heard his name,” Mr. Apatow said, adding later that the company is “so central to my life. It threw me. It was like suddenly being introduced to the person who invented fire.”

The nerd in me is wondering if Apatow is just talking about Gmail (the obvious entry point), or if most of his work is stored and shared in Google Docs. Regardless, what better advertising for Google’s services than proof that the rich, creative and powerful rely on them? More important: what better proof that, whether they like it or not, the technology and entertainment industries are intertwined?

How Books Will Survive Amazon ⇒

Joel Epstein published this excellent piece at the New York Review of Books yesterday. He manages to break down some of the more dubious dark corners of the Department of Justices suit against Apple and the major publishing houses without getting too deep into the weeds of legalese.

Here he describes what books will look like in the near future:

Independent editorial start-ups posting their books on appropriate web sites have already begun to emerge and more will follow. The cost of entry will be slight. The essential capital will be editorial talent and energy, as it had been in the glory days before conglomeration when editors were themselves de facto publishers, publicists, and marketers. Many start-ups will fail. Some will not. Specificity, reflecting the structure of the web, will matter: a guide to the cultivation of daffodils will more likely succeed than a more diffuse gardening title.

The digital revolution is having the same effect on movies. Keywords: talent and energy. That’s a future that doesn’t look to bleak to me.

Try Getting 24 FPS Right First

NATO Logo

Going to the movies in the 21st century is an abysmal experience. The ticket prices are absurdly high, concession prices and sizes have reached outrageous levels and the bread and butter of the movie going experience, getting an image to appear on a big screen, is no longer reliably accomplished. Even for someone who loves movies, going to the multiplex just plain sucks.

I suppose it comes as no surprise to me, then, that the main focus of CinemaCon, a conference put on by the National Association of Theater Owners (NATO), has been a new projection technology that could become a lucrative box office draw. As you may have heard, 10 minutes of Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit was projected at 48 frames per second for an audience of theater owners, studio executives and journalists there earlier this week. Jen Yamato has a nice summary of reactions over at Movieline:

The footage, preceded by a taped introduction by Jackson, drew breathless raves for portions of aerial footage whisking, in the style of an IMAX nature doc, over wide landscape shots that seemed to prompt unanimous praise. Then came the character footage, which told another story: At its increased frame rate, Jackson’s 48-fps scenes were reportedly almost too realistic, approximating what many compared to an HD TV or television soap-like quality.

That the footage dropped with a thud is no real surprise. Shooting and projecting images at twice the frame rate that became de rigeur some 90 years ago is going to look shockingly different. If an audience of industry professionals was turned off by the visual shift, will audiences be able to handle it?

Since I haven’t seen the footage I can’t really speak to whether or not 48 fps might be the “next big thing,” albeit presently misunderstood. If I had to guess, I’d bet it actually is a stunning advancement for work that demands it, but something as gauzy and filmic as The Hobbit may not be a project that jibes with the hyper-real look it offers.

The truth is that I don’t care about bringing this technology to the multiplex right now. NATO needs to clean up its own house before it starts shooting from the hip. I get that the goal of CinemaCon is to wow execs and journos, but would it have been so bad if they converged on Las Vegas with the main goal being to figure out how to smooth out the kinks in the digital transition?

You may recall the revelation last year that AMC, the second largest movie chain in the US, had a problem switching out their 3D lenses during 2D presentations, resulting in significant light loss and an overall darker picture. Here’s my favorite quote from an AMC projectionist after the wrong film played with the wrong lens at a screening of Tree of Life in New York City:

Even if it’s not a 3-D movie, if it’s a 3-D projector the 3-D lens is still used. If it’s a 3-D house we have to use a 3-D lens. I haven’t had any complaints about the 3-D lens making 2-D movies dark.

While I didn’t go poking around in the projection booth afterwards, I’m pretty sure that I recently saw Cabin in the Woods with the wrong lens on the projector. I was suspicious because I had seen the movie at SXSW projected on film and I noticed a marked difference in some of the film’s darker sequences. Unsurprisingly, I was at an AMC. Of course, by not complaining, I become part of the problem, allowing this projectionist to go about saying everything is just fine with using the wrong lens. But who wants to police movie theaters?

AMC and other NATO theater chains should be ashamed. They’re not providing a decent product anymore. Even if 48 fps was a hit with the crowd at CinemaCon, I wouldn’t trust these theater chains with it.

The relationship between theater owners and movie-lovers is one of trust, and NATO has lost it. It’s time to earn it back. Put down the shiny new technologies and figure out how to project movies correctly, at every screening, in every theater in the country. That would be something.

Tribeca 2012 Review: Supporting Characters

Supporting Characters Still

There are a few different ways a film can suck, but for the sake of argument I’d like to boil it down to two:

- The above-the-line talent was more concerned with getting into festivals/getting bought than making a coherent piece of work.

- The above-the-line talent made a film they believe in and the resulting film is maybe not so great.

Daniel Schechter’s Supporting Characters, thankfully, falls into the latter category. It’s has its issues and spends the last thirty minutes trying to pay for its sins, but overall it’s an honest piece of work. The problems I have with it are ones that could only be corrected by Schechter making a different film. I’m glad he didn’t because what we have is a mostly enjoyable, if sloppy, piece of work.

The film follows Nick (Alex Karpovsky), a sought after editor of broken (read: shitty) films and Darryl (Tarik Lowe), Nick’s best friend and assistant editor. The two are trying to get a romantic comedy in the can while navigating the murky waters of their personal and professional relationships. Nick can’t help but let his eyes stray from his fiancé, Amy (Sophia Takal), when the film’s star Jamie (Arielle Kebbel) starts tossing pheromones his way. Darryl, meanwhile, is in a destructive relationship with Liana (Melonie Diaz), a dancer who can manipulate him at her whim.

Supporting Characters is about men and the women that get in their way. Sophia Takal, herself a talented filmmaker, is excellent as the adorable and supportive Amy. For my money she makes for a great Anna Kendrick stand-in and is someone who should be getting roles in more sophisticated work. Nick’s problem with Amy seems to be that she’s too supportive. She begrudges that he gets to sleep in and bumble about their spacious Upper West Side apartment, but that’s the extent of her criticisms. Nick isn’t just annoyed by her; he seems to loathe her and avoid her for reasons I can’t understand.

In almost every film he is in, Karpovsky plays a nudnik who is funny enough to get close to beautiful women and plain enough that the weak ones will sleep with him. Here he is a feeble and manipulative editor, but he is so good at convincing women that he is clever that he never sleeps alone. He makes for a very unsympathetic hero. His conflict is whether or not he should bang a movie star or stay engaged to a gorgeous and supportive woman, or do both and cover it up.

Darryl, on the other hand, is the weakling of the team. As Nick’s second fiddle, he is so unsure of himself that he would rather remain in a destructive relationship than be alone. Tarik Lowe, who also co-wrote the film with Schechter, does a great job of bringing this character to life. He’s not too complicated, but clearly he has an axe to grind with his lot in life. As good as Nick tries to be, he is ultimately a jerk; watching Darryl reconcile this fact with his own business is the more interesting storyline.

If you ask me whether or not I think Supporting Characters is a good film, I’ll tell you that I don’t think it is. I can’t get over how uninteresting the women are and how annoying Karpovsky’s character is. But it’s an honest piece of work made by a filmmaker who seems sure of himself. That is commendable, and I’m excited to see Daniel Schechter’s next project.

Shawn Blanc on Clicky Keyboards ⇒

Shawn Blanc just published the clicky keyboard blog post to end all clicky keyboard blog posts:

Mechanical keyboards like the Das are bulky, loud, and fantastic for typing. Compared to the slim Apple keyboards, the Das is different in every way except that the end result is still the same: words get onto the screen.

I’ve been interested in a Matias Tactile Pro 3 for years,1 but I’ve never had the guts to shell out for it. Shawn offers in-depth perspective on the three big Mac mechanical keyboards: the Tactile Pro, the Das Keyboard and the Apple Extended Keyboard II.2

I’m sure I will revisit and reread Shawn’s post many times before I finally break down and buy one of these keyboards. Frankly, if the Das wasn’t so needlessly ugly (unlike Shawn, I can’t get over the ridiculous typeface on the keys) I’d probably order one right now.

But I need to stop shopping and just write, right?

-

I use Apple’s current model aluminum keyboards if you must know. I have a USB with numeric keypad one at home and a bluetooth one I use with my iPad. ↩︎

-

He skipped the buckling spring SpaceSaver M. Too nerdy? ↩︎

Tribeca 2012 Review: Consuming Spirits

Consuming Spirits Still

I like to whine about how “Hollywood” the Tribeca Film Festival is, about how similar most of its Amer-indie slate feels.1 As many workshopped talkies as one may endure, this is still New York City, historically a hotbed of experimental cinema. There is no handbook for these adventurous filmmakers; no one telling them the gun must go off in the third act. It is this freedom that allows them to come up with some of the wildest films imaginable and execute them on a (sometimes literal) shoestring.

Chris Sullivan’s Consuming Spirits is listed as an experimental animation, but I think that’s a bit of an unfair description. While its technique of handmade 16mm animation certainly qualifies it as a trial in patience, it is, at its core, a narrative. The “experiment” is a mere playfulness with time, scale and reality; it may even be too tame to be considered all that experimental in some circles. I imagine it is listed as such because no one else in the fest wanted it, and that’s a shame.

As a narrative Sullivan’s film is an invigorating experience, unencumbered by the silly rules we’ve imposed on the storytelling process. It is a 130 minute portrait of a small Appalachian town whose inhabitants are as gruesome as they are endearing. Sullivan employs stop-motion, paper-craft puppetry and hand-drawn animation to tell his tale, each form placing the audience in a different temporal and/or emotional realm.

The film tells the story of a small Appalachian town called Magguson. When Gentian (or Genny) Violet, a Jane-of-all-trades who drives a schoolbus, works at the local newspaper and gives tours at the museum, hits a transient nun on the road one night, she set off a chain reaction that ultimately unravel’s one family’s well-hidden dirty laundry. Part thriller, part family drama and part dreamscape, Consuming Spirits is like no other film I can recall.2

Sullivan isn’t without a sense of humor; in fact he’s downright puckish. The title itself is a pun and the film is peppered a few good laughs few geared directly at the cinephile set. Like the scene in which one character picks out a skin flick featuring mental patients putting on a lascivious show: “Titty Cut Follies.” Fake porno titles are a comedic past-time at this point, but the humor here is brilliant. By invoking Frederick Wiseman’s groundbreaking documentary, Titicut Follies, Sullivan gets more than a cheap laugh; he ties in the horrors of a sanatorium without having to show it to you. (Magguson has a sanatorium that plays a central role to the film’s plot.)

The animation itself is astounding. Sullivan’s characters are monstrous and beautiful. Their faces are creased and pocked with bags under their eyes, their teeth yellowed or blackened or barely there. These paper stand-ins are imbued with all the frailties and deformities of humans. Perhaps it is their closeness to how people actually look, warts and all, that makes them so tough to look at. They are more mirror than they are lens unlike, say, the airbrushed hardbodies we see at the multiplex.

The hand-drawn segments are less invigorating, but nonetheless wild to look at. As the narrative unfurls, the form comes into sharper focus, making it a bit clearer why different techniques are employed. It’s a deft move and one I appreciate more now that I have digested the film a bit.

Chris Sullivan spent almost fifteen years making Consuming Spirits and it’s a marvel to behold. All movies are hard to make, so he doesn’t get bonus points for taking his time. However, by not relenting when the technology changed, by seeing his vision through after all these years, Sullivan brought to life a unique piece of work that I am glad wasn’t rushed.

Finally, this project was funded in part by the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation and a recent Creative Capital grant. Money. Well. Spent. Consuming Spirits is a piece of work that is a hard sell for anyone. Champions of experimental film are few and far between compared to the billions investors pour into the blockbuster and indie markets.

This is not only a great piece of art, but it’s a great movie that I think could be seen by any kind of audience, even those who wouldn’t be caught dead watching an “experimental film.” I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that those who support this kind of work deserve a pat on the back. We shouldn’t have to wait another fifteen years to see what else Chris Sullivan has to offer. Here’s hoping we won’t.

Text & Death

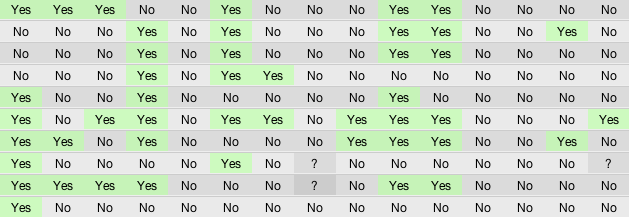

iOS Text Editors

I can’t be the only one who looks at Brett Terpstra’s prolific iOS text editors comparison chart and thinks of his own mortality, can I?

If you haven’t seen it yet, the chart in question is worth a peek even if you don’t care about iOS text editors. The methods Terpstra used to build the thing prove what a web wizard he really is. Most of the info was crowd-sourced into a Google spreadsheet and then built straight into the niftily designed chart. It’s an excercise in efficiency, a sort of data parkour.

What strikes me is the absurdity of the chart itself. It’s massive, covering not only every known text editor in the App Store but also every feature. And it gets pretty granular. “Reading Time,” the ability of an app to display the approximate time it will take to read the current document based on its length, gets its own row, for example.

I’m not here to mock Terpstra’s product. Not at all. It is an invaluable snapshot of what is available right now in an increasingly cluttered marketplace. As I’ve written before, I buy a lot of text editing apps. I use them all for different writing tasks or to cater to my different moods.

What freaks me out is how excited I was when Brett published his chart. Looking at it, all I can think is how ridiculous the whole plain text craze has become. I’m as guilty as anyone of obsessing over the tiny details in these apps, and I love that there is now a resource where I can quickly drill down the exact feature I need. Here’s the thing, though: the perfect text editor doesn’t exist.

I should know, I’ve bought (almost) all of them.

If I’ve learned anything from perusing Brett’s chart, it’s that I need to stop worrying about apps and just write more. It really grates on me when people spout motivational platitudes like that1 but I think it’s applicable here.

Life is short and the considerable time I spend wondering which app has the best Markdown implementation2 is time thoroughly wasted. Write more, shop less; all of this will end someday.

So thanks, Brett, for the perspective.

Rules to Break ⇒

{% blockquote Bilge Ebiri http://ebiri.blogspot.com/2012/03/narration-voiceover-and-shape-of-world.html Narration, Voiceover, and the Shape of the World %} Many claim that voiceover (and I am cheating a little bit here by using “voiceover” and “narration” as interchangeable, even though they’re somewhat different things) is not very rigorous, and yet some of the most rigorous films ever made – Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest and A Man Escaped, Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad – utilize it. We mouth to ourselves the idea that there’s something impure about narration, but when it pops up in the right situation we embrace it. Sometimes I wonder if we just create these rules so other people can break them. {% endblockquote %}

I’m as guilty as anyone of rolling my eyes when I hear voiceover narration, and in many cases it’s because I ascribe to the exact “rules” Ebiri calls into question. Perhaps I am simply disappointed in how poorly this uniquely cinematic technique is often employed, not with the technique itself.

I’m glad Ebiri took the time to thoroughly discount the belief that voiceover is inherently flawed or a lazy crutch, offering some great, classic examples.

(via Matt Zoller Seitz.)

The Piracy Conversation

Doinel Taking Milk

Not every piece Matt Singer publishes over at Criticwire makes me want to respond in kind here, but most of them give me an itchy trigger finger.1 This afternoon, he posted a piece flatly titled “Is it Okay For Critics to Pirate Movies?” which brings the critical community (back) into the never-ending shitstorm that is The Piracy Conversation.

Mind you, his is a response to Mike D’Angelo’s braggadocious “Critic’s Notebook: Is It Wrong to Download Pirated Movies? Not Quite, Says One Critic” from last week.2 The gist of D’Angelo’s piece was that he doesn’t “feel terribly guilty about downloading high-def copies of films that nobody in America has any interest in renting to me.”

Back to Singer for now. He dips his toes in with a bit more gravitas than D’Angelo’s I’m-right-because-I-want-to-be-right boorishness:

Should a critic have access to any film he wants? A critic’s talents are directly proportional to his or her film knowledge. But financially speaking, film criticism is in even worse shape than video retail. Film critics can’t afford to drop $40 a pop for Criterion Blu-rays. Does playing by the rules doom a film critic to a certain degree of ignorance?

I think we should decouple criticism from piracy. Sure, we write about this stuff and maybe turn a few pageviews into precious pennies (or get paid in burgers or, less often, crisp twenty dollar bills), but does that really pose any more of a conflict? There are rare instances when I think the two are part of the same conversation, like when a critic reviewed a leaked workprint of X-Men: Origins: Wolverine in 2009 (hey, 3 years ago yesterday!). Otherwise, what we’re talking about is a practice whose critics say shouldn’t be done by anyone, anywhere, ever.

That being said, most of us whining to the wind about this are absolutely students of cinema. We love the medium and we aim to see as many films as possible, often bragging to one another about how many and how often because we really want people to know. We can’t afford to own every film ever (though some try to) so we go out of our way to be able to see films on the cheap. We spend a day at the multiplex theater-hopping, we get credentialed at festivals, we write for free in exchange for screenings, we get publicists to send us their storeroom. How else do you expect us to see this stuff?

The Piracy Conversation got out of control on Saturday when Kim Voynar published a response to D’Angelo, “Piracy, Again? Arrrrrggggh.” She argues that the world is crumbling around us and thereby movies aren’t important, or something.3 There’s really no sense in arguing with people at the polar ends of this debate. Blog posts about piracy rarely resolve anything or, for that matter, make a point, but they’re good for pageviews and comments. So around we go. (Keep reading, though!)

All of this talk got me thinking: what would Antoine Doinel, François Truffaut’s hero and career-long on-screen doppelgänger, do?4 I’m not quite sure why my mind immediately goes to such a morally dubious character. I never played hooky as Doinel did, or stole milk or concocted a plan to hock a pilfered typewriter. But, if his crime were sneaking into the movies, or stealing them, would I condemn him for it? Truffaut was perhaps the quintessential student of cinema, who lived for a time, as his fictional counterpart, on his wits alone. The number of films he was able to pack in through his youth would astound even the most voracious pirate today. Are we supposed to believe that all of his receipts squared with the number of films he saw?

It was a different time, though! Truffaut and his pals had the Cahiers du Cinéma and Bazin and Langlois and the Cinémathèque Française.

Right. And we don’t.

We are living in the golden age of free-flowing information. Like it or not, almost every film available digitally, and many that aren’t, is available for download from some source, somewhere. These films are there for the plucking and, for now, if we call downloading it a crime, it’s one with almost no consequence to the perpetrator. It’s a student’s paradise: an endless library of movies, a digital cinémathèque.

What would Doinel do? He would probably see as many movies as he could until he inevitably got caught (as he is wont to do). Why shouldn’t we?

Now, there are reasons not to pirate. The irony, of course, is that while we soak up all of that knowledge off of pirated films, we are supposedly eroding the very industry we would like to be a part of. I, for one, don’t believe that that’s true, though I get that there is fear from Hollywood and “content creators.” Too many movies are making too much money while being traded wildly across the ether. Still, I firmly believe even the poorest cinéphiles should support their local repertory theater/video stores/artists. That’s not always the opposite of piracy, but when it is I think you should always choose to support the arts, directly, with cash.

Both sides of The Piracy Conversation consistently make the mistake of trying to own some piece of moral grounding. D’Angelo gets it wrong because he blames companies for not adapting to his needs; Voynar is off her rocker playing the equivalency card, holding cinéma up as not that big a deal when compared with poverty, disease and womens’ rights, which she does confidently presuming she unquestionably has the moral high ground.

This is an issue that is far from black and white. Anyone who suggests otherwise hasn’t really considered the question. What about films that aren’t public domain but have never been released on home video, thus have no financial impact if traded among cinephiles? What about a film you already own but need in a different format; or the disc is scratched? What about a film you made and you don’t mind? Maybe pirating films is morally questionable and we’re all just going to have to learn to live with that. Would that be such a bad solution?

Which brings me back to The 400 Blows. Why did Antoine Doinel steal milk his first night on the street? Probably because he needed a drink.

-

Which is why I love reading the site, mind you. ↩︎

-

Which was actually a followup to one of D’Angelo’s earlier posts. Piracy posts all the down, basically. ↩︎

-

“We are at a period in our history where we are at the cusp of either uniting for a major revolution that will profoundly shift the way in which our societal structure is organized, or plummeting headfirst into a future where the Christian right controls our lives and sets the rules under which we live, or possibly just destroying our planet over religious differences, war and good old-fashioned avarice. And your biggest problem is whether you’re able to rent Anatomy of a Murder on freaking Blu-ray? For real?” ↩︎

-

Specifically Doinel in The 400 Blows. ↩︎