Review: “Waves (Response to a Blog Post)”

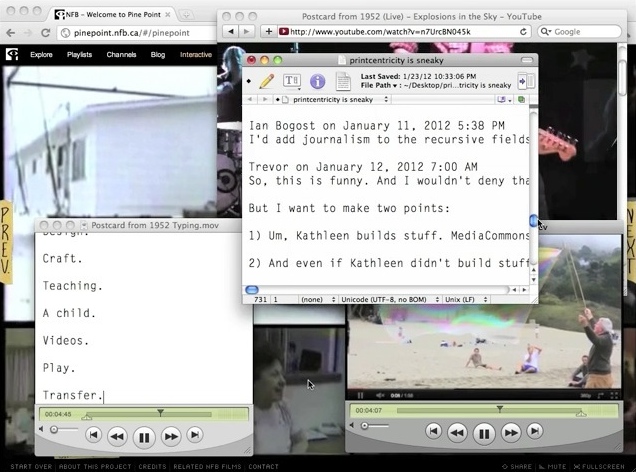

Still from “Waves (Response to a Blog Post)”

I’d like to talk about Daniel Anderson’s short video essay, “Waves (Response to a Blog Post),” which he released a week ago on Vimeo. First, let’s take a look at it, shall we?

{::nomarkdown}

I first watched this film on my television, comfortably sitting on my couch. I tensed up almost immediately, succumbing to a kind of claustrophobia. This digital work, this “screencast,” is something I relate to viscerally. As a writer and, particularly, as a blogger, “Waves” illustrates the work I do on computers in a way I hadn’t conceived of before. It’s…frightening.

Here is Mr. Anderson’s description of the film:

This is my response to the blog posting, The Digital Humanities and the Transcending of Mortality. See the mantra: you don’t study digital composing, you perform it.

The post in question was published on January 9 by Stanley Fish at the New York Times. In it he discusses scholarship in the digital age and why he has opted to reframe his “column” as a “blog.” He ends his piece with a question or, perhaps, a challenge:

The pertinent challenge to this burgeoning field has been issued by one of its pioneer members, Jerome McGann of the University of Virginia. “The general field of humanities education and scholarship will not take up the use of digital technology in any significant way until one can clearly demonstrate that these tools have important contributions to make to the exploration and explanation of aesthetic works” (“Ivanhoe Game Summary,” 2002). What might those contributions be? Are they forthcoming? These are the questions I shall take up in the next column, oops, I mean blog.

“Waves” appears to be the answer to that loaded question. Consider what the film is: it’s a window onto the desktop of a scholar who is mashing up and remixing the work of others in almost every conceivable way. The text, the music, the videos, the applications and even the graphical interface itself are wholly unoriginal, conceived not by the filmmaker but by other artists. Any one of us could replicate the work that Anderson performs in his film, but why would we?

Taking it further, we can talk about the way that Anderson released this work into the world. It was uploaded to Vimeo, where many would be watching it on a computer screen. The experience changes if you watch it on a tablet or on a television; it is completely different if you watch it windowed or fullscreen; and the experience of watching this either on a Mac or a Windows machine alters the viewer’s perspective even further. The portal through which we view the work completely changes the experience. If the challenge is that scholarship will ignore digital technology “until one can clearly demonstrate that these tools have important contributions to make to the exploration and explanation of aesthetic works,” then I’d say that burden has been met.

I spend a great deal of time in front of screens. When I’m not in front of a computer, I am usually watching television or tapping away on my iPad or iPhone. Digital tools surround me because I like them and they enhance the way I work and live. No matter what the screen, I am always aware of my surroundings. The coins and papers on my desk, the subway train on which I clack away on my iPad, the park from which I am tweeting, etc. The screencast, however, disembodies the act of making a digital work. Anderson’s film feels corpse-like, a computer almost running itself for its own amusement and gains. Like I said, it is frightening, but I can’t look away.

According to his Web site, Daniel Anderson is an English professor at the University of North Carolina where he studies “new media composing and instructional technology.” His aim here may have been academic, but I would argue that the outcome is entirely cinematic. There are a severe amount of interpretations that “Waves” is open to which only adds to the joy of experiencing it. Plop ten people down in front of this film and you’ll get at least ten different explanations, maybe more. Now that’s cinema.

Rob Corddry: Fan of Screenplay Markdown ⇒

Meanwhile, at Macworld:

Of much interest to Corddry was the fact that developer Brett Terpstra, Jonathan Poritsky, Stu Maschwitz and Martin Vilcans on bringing Stu’s Screenplay Markdown proposal to his popular Markdown editor Marked. Terpstra announced, in a quick back-and-forth with Corddry that they were also working on getting a Markdown exporter working for Final Draft.

Well, now that’s exciting! I can’t say I’m surprised. It was Corddry who, in conversation with Merlin Mann, said, “We are slaves to the worst piece of software ever created: Final Draft.”

Hollywood Budgets Visualization Challenge ⇒

Whoa:

{% blockquote The Information is Beautiful Awards http://www.informationisbeautifulawards.com/2012/01/challenge-of-the-stars/ %} The Oscars are looming. So we thought it might be great to produce some amazing, hand-curated data on Hollywood films.

Our ultra-comprehensive dataset lifts the lid on opening weekends, worldwide gross, budgets, storylines, review scores – everything – for every Hollywood film released in the last five years.

…

Our challenge to you is, as ever, VISUALIZE. {% endblockquote %}

The fine geeks at Information is Beautiful have culled data on every film released since 2007 from The Numbers, Box Office Mojo, Wikipedia and IMDb. They’ve placed it all nice and neat into a Google Docs spreadsheet. Entrants have until February 6th to take the data and either create a static graphical representation of it or build a webapp.

If my 2011 Box Office in Review didn’t tip you off, I love playing with data. When I was parsing out the numbers myself, I created a spreadsheet on my own and it took forever. This dataset is nice to have even if you don’t want to make a neat infographic out of it. But you do; obviously you do.

They extended the contest deadline to widen the pool of entrants:

{% blockquote %} We’ve had loads of great entries already. And some amazingly creative ideas are popping up.

Like, Jermone Cukier‘s explorations of the dollar value of individual features of a plot. He cross-referenced keywords for each movie on IMDb with box office return. The result? A price tag for each plot element.

Having an explosion in your film could earn you $150m, he finds. A love triangle $37m. And a psychopath – just $32m. {% endblockquote %}

I cannot begin to explain how excited I am to see what people come up with. I may have to enter myself.

Hollywood Still Hates You ⇒

Matt Drance, commenting on the new Warner Brothers deal with Netflix that not only delays rental availability by 56 days but also restricts adding their films to your queue until 28 days after release:

Also under this new deal, pirated movies remain free of charge, free of non-skippable ads, free of five-minute load times, and are now nearly three months ahead of the competition.

Hollywood is making it harder and harder to support their work.

(via Ben Brooks.)

Passive Listening ⇒

Great article on the digital music business over at The Verge:

{% blockquote -Paul Miller http://www.theverge.com/2012/1/26/2740981/debate-spotify-mog-rdio-kill-save-music-industry The Verge %} Spotify is doing similar work on “radio” playback. “Radio contributes to the overall music discovery experience,” a Spotify representative told me, “which is why Spotify Radio has recently undergone a top-to-bottom overhaul making it a bigger, smarter and an altogether cooler music discovery experience.”

Rdio’s on board as well: “Passive listening is something that’s critical in the overall experience,” says Drew Larner, the service’s CEO.

Despite Pandora’s big head start, the huge libraries and lack of radio-style licensing restrictions on for-pay streaming services means there’s a ton of opportunity here to offer something people have never heard before — namely, everything. And the seamless operation is a big leg up on ad hoc music piracy: “Even if 14 million songs were free, people would still gravitate to radio services,” says David. “I hate to say it, but my mom listens to the music stations that come with her cable TV.” {% endblockquote %}

I think “passive watching” might be the missing piece of the streaming video pie. Americans may watch 4-5 hours of cable a day, but how much of it is actually “active.” I like to keep reruns of Law & Order on while I’m doing dishes, for example.

Champions of on-demand streaming services cite the ability only watch what you want and nothing else, but even choosing what to watch is an active process. I think the game-changing set-top-box will be the one that starts playing video the moment you turn it on. That’s the comfort that keeps so many people tied to cable.

Businessweek Profiles Amazon's Hit Man ⇒

{% blockquote -Brad Stone http://www.businessweek.com/printer/magazine/amazons-hit-man-01252012.html Amazon’s Hit Man %} “What we’re building is more like an in-house laboratory where authors and editors and marketers can test new ideas,” says Jeff Belle, vice-president of Amazon Publishing and Kirshbaum’s boss. “Success to us means working with authors who want to find new ways to connect with more readers.”

Talk like that hasn’t mollified publishers, and it’s easy to see why. They’re trying to protect a century-old business model—and their role as nurturers of literary culture—from encroachment by a company that consistently reimagines how industries can be run more efficiently. {% endblockquote %}

Gosh, that sounds a lot like the movie industry, doesn’t it? This whole artlicle is a great read, highlighting the challenges that come with trying to move a stubborn 100+ year-old industry into the future. So many memorable lines in it, like this one from author Tim Ferriss of 4-Hour Workweek fame:

Amazon will publish his new book, The 4-Hour Chef, in September. “For me it was a choice between publishers embracing technology and a world-class technology company embracing publishing,” Ferris says. “The latter will give me more of a chance to improvise and experiment.”

Reading Netflix's Shareholders' Letter

Netflix Logo

Every time one of these comes out, we learn a few interesting tidbits about Netflix and the video industry as a whole. For the first time in a while, this letter wasn’t utterly depressing. The company and CEO Reed Hastings seem to have stopped the exodus of users after last summer’s Qwikster blunder, and in fact are gaining users again. They are still company to beat in this space.

So, what’s so interesting in the Q4 2011 shareholders letter (PDF)?

The Numbers

Netflix added 220,000 streaming subscribers last quarter but lost 2.76 million DVD/Blu-ray subscribers. It’s possible that a lot of those customers are seeking out other ways to get physical media, but I’ll bet the majority are moving to streaming only for all their content needs. This is why Netflix wants to be a streaming only company.

The DVD/Blu-ray business is actually a lucrative one. There may be fewer physical disc subscribers but the are worth much more than streaming ones. In raw numbers, the 21.67 million streaming customers brought in $52 million in profit while 11.17 million DVD/Blu-ray subscribers pulled in $194 million. For every dollar of profit a streaming subscriber is worth, a disc subscriber is worth $7.23. That’s a huge difference.

So the numbers actually tell a good story. Physical media is proving to have decent staying power. DVD and Blu-ray aficionados will be happy about that. Personally I think Blu-ray’s picture quality is far superior to streaming so I prefer to get discs for visual feasts.1 Plus, growth is the only thing that matters in Silicon Valley. As long as Netflix keeps adding streaming subscribers, they’ll be just fine.

Amazon to More Directly Compete with Netflix

This is the first I’m hearing anything like this:

We expect Amazon to continue to offer their video service as a free extra with Prime domestically but also to brand their video subscription offering as a standalone service at a price less than ours.

Amazon Prime Instant Videos actually is already cheaper than Netflix Watch Instantly at $79 per year. At $7.99 per month, Netflix comes to $95.88 over 12 months. If Amazon ends up offering a low monthly rate for only streaming video (Amazon Prime’s price tag also includes free 2-day shipping on all orders and access to the Kindle Lending Library) that could certainly heat up competition between the two companies. However, as Netflix’s letter wryly notes, neither Amazon nor Hulu offer as compelling a streaming library…yet.

Netflix Really Hates Ads

Looks like Netflix agrees with me:

In the case of Hulu Plus, subscribers have to pay for the service ($7.99) and still watch commercials (unlike, commercial-free Netflix). Even if Hulu could afford our level of content spend, at the same price consumers would prefer commercial-free Netflix over commercial- interrupted Hulu Plus.

Hulu Plus does pose a threat to Netflix, but ideologically they are very different. Just look at how each company talks about its customers. Whatever problems I have had with Netflix, I have never felt that they don’t respect me as a user. Take this, for example:

Constantly improving our service is key to satisfying current members and attracting new ones. The better we make the Netflix experience, the more hours are watched, translating into increased retention and strong word of mouth referral.

Classy, and true.

Streaming TV is About to Get Awesome

Over the next few years, UIs will evolve in astounding ways, such as allowing viewers to watch eight simultaneous games on ESPN, color coding where the best action is in a given moment or allowing Olympics fans the ability to control their own slow-motion replays. A decade from now, choosing a linear feed from a broadcast grid of 200 channels will seem like using a rotary dial telephone.

Yes, please. This sounds straight out of Back to the Future Part II.

Facebook Integration is Coming to the US Soon

Apparently the US is the only market in which Netflix isn’t able to automatically share out what you’re watching on Facebook thanks to the Video Privacy Protection Act from 1988 (VPPA). That may change soon though.

A broad bipartisan group of lawmakers from the House recognized the benefits of modernizing and simplifying this law and passed H.R. 2471, an amendment to the VPPA that clarifies the ability of consumers to elect to share their viewing history on an ongoing basis if they so wish. Now this proposed amendment is with the Senate, and they have scheduled a hearing on the VPPA for next week.

Here is the original VPPA (introduced by Patrick Leahy of PIPA fame, actually) and the new legislation that would amend it. As Netflix gets more social, I wonder what will become of movie sharing services like Miso, GetGlue and Letterboxd.

The good news about the US being the last to implement Facebook integration is that it sounds like it will be well refined by launch time.

In the UK and Ireland we launched with our best Facebook implementation to date.

Any UK readers have experiences to share?

Programming Paradigm Shift

Netflix’s first original series, Lilyhammer, starring Steven Van Zandt, starts February 6th. I had been wondering how Netflix would be rolling out new series. It turns out, at least in the case of Lilyhammer, they will make the entire first season (eight episodes) available at once.

Netflix members can enjoy the first season as quickly as they like, instead of having to wait a week for each new episode as they would with linear programming.

This hadn’t occurred to me, but it actually makes a lot of sense for web viewing. Part of the success of television on DVD and on streaming services is that users can watch at their own pace. This could be Netflix’s ace in the hole; not only do they have exclusive content but they have a superior way to deliver a show to you, one season at a time.

Television’s drama revival in the last few years in part reflects a narrative shift to epic, multi-hour threaded plot-lines. Netflix may be on to something huge here. The stories that television creators want to tell have been retrofitted into the weekly release schedule that has been the cornerstone of broadcasting for decades. That could change.

Conclusion

2012 is going to be a big year for Netflix. Now that Qwikster is just a bad memory, Hastings and his team have put the company back on an exciting trajectory. Cant wait to see what happens.

-

Tree of Life, for example. ↩︎

Brad Bird Responds to Typographer

Over the last few days, this conversation has grown on Twitter:

Matthew Butterick, remember, is the typographer who wrote the letter to Brad Bird about his use of Verdana in Mission: Impossible - Ghost Protocol. Hoefler & Frere-Jones is one of the top type foundries in the world, so it’s nice to see them add their perspective on the issue of on-screen fonts.

There’s a lot of sniping here, but I think it’s a good thing that these respective heavyweights are having a public discussion about film typography. I’m a fan of Bird’s work and of Ghost Protocol, but I think he’s in the wrong here. His dismissal of fonts seems boorish. Not only will he not defend his work, but he shrugs off the question of his choice: “I was shown a few sans serif fonts and I picked the 1st that didn’t bother me!”

If it’s in the frame then the onus is on the director to make a deliberate and defensible choice. Bird is asking for a free pass.

The devil really is in the details.

(h/t commenter “tejas” on Baradwaj Rangan’s Web site.)

The R is for Rights

Yesterday, Nilay Patel over at The Verge posted a piece on the return of Digital Rights Management (DRM). He speaks with Mark Teitell from UltraViolet about Hollywood’s newest attempt to impose restrictions on the files they sell.

Why did the movie industry spend several years and millions of dollars building a system no more effective at stopping theft and less flexible for consumers than no system at all? Teitell told us that without DRM, “the business of producing compelling video content couldn’t pay for itself over time,” and said that the “big guiding belief” behind UltraViolet is not stopping piracy, but rather presenting “a truly compelling legitimate alternative for those consumers that weren’t fixated on stealing — they want freedom and flexibility, and we’re giving that to them.”

Bullshit.

Without DRM video couldn’t pay for itself? Patel points to the fact that the music industry is on the mend even though it has done away with DRM, but this used car salesman just spouts more nonsense. “The R is for rights — people like rights. We have the Bill of Rights.” Uh huh.

Video can absolutely “pay for itself over time,” but it can’t pay the salaries of the uncreative paranoid millionaires who run the studios. No one wants restrictions on their files, not even these fantasy “consumers that weren’t fixated on stealing” he mentions. People want to own the things they buy. DRM subjugates video ownership to the studios, removing the consumer’s rights. Perhaps Teitell should read the Bill of Rights one more time before whipping that line out again.

The company that gets this right and does away with DRM will make a whole lot of money. Enough, I’ll bet you, to finance a lot of great, original work.

The War Against 35mm ⇒

{% blockquote -Richard Jenkins http://www.littlewhitelies.co.uk/blog/bad-rep-the-war-against-35mm-17746 Little White Lies %} The view from the gutter, that is from those tortured souls for whom an integral part of the cinema experience is watching a film screened from a print (and, perhaps more importantly, have no interest in Avatar), is that the industry invariably views serious cinephiles as cranks, dilettantes and dreamers with no real concept of the fiscal realities of contemporary distribution. Yet one puckish tweet cuts straight to the heart of the matter: “Hey guys, it’s cool, we’ve got paper. No more need for canvas.” {% endblockquote %}

It feels like other industries have done very well by “cranks, dilettantes and dreamers.” Music, publishing and gaming come to mind. That you can buy new albums on vinyl but won’t be able to see a 35mm print soon is beyond me.